Rare moment: the knock inside the tree

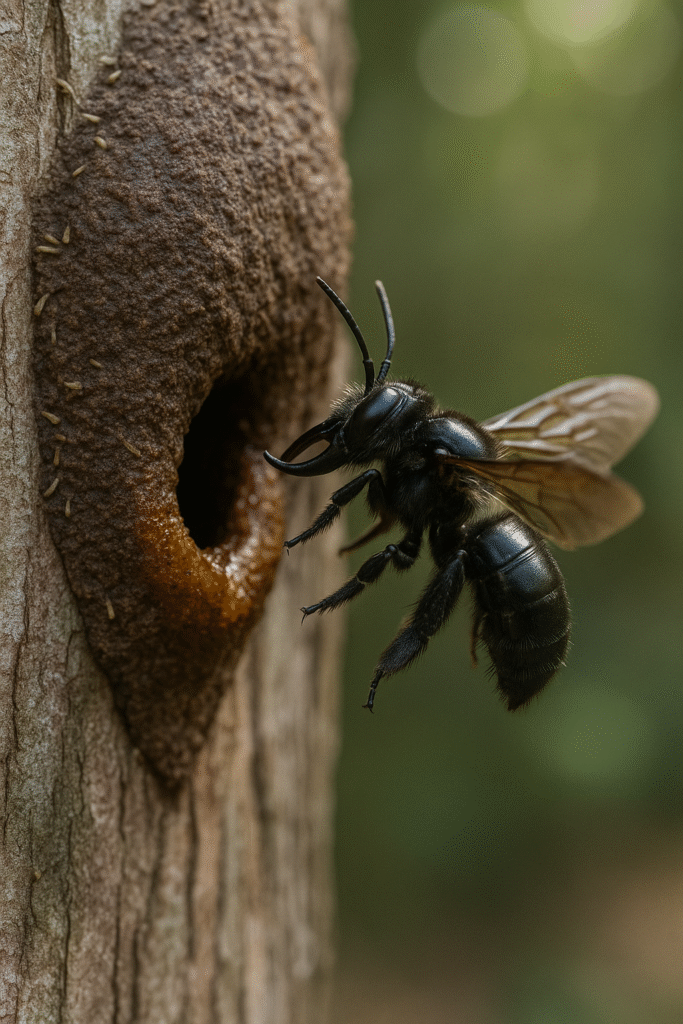

We were deep in coastal forest, where heat stands like a wall and cicadas make time vibrate. Halfway up an ironwood trunk bulged an arboreal termite nest, the size of a backpack. A soft clack… clack came from inside—like a finger tapping wood from within. Then a black, heavy shape pushed out through a sap-glossed entrance: a female Wallace’s giant bee, jaws wide as thumbnail clippers, wings flickering with the low rumble of a trapped storm. She hovered, circled us once with inspection-level calm, and then hammered off into the canopy. Ten seconds; history reassembled in amber and muscle.

For most of the 20th century, this bee—the largest on Earth—was a rumor with a Latin name. Its rediscoveries proved something rare and useful: the forest still holds secrets if we leave it enough unbroken sentences.

Identity: what Megachile pluto is (and isn’t)

- Family: Megachilidae (leafcutter and resin bees).

- Size & look: Females up to ~4 cm long with huge sickle-shaped mandibles and a glossy black body; males smaller and slimmer.

- Range: Patchy forests of Indonesia’s North Moluccas (e.g., Halmahera archipelago).

- Lifestyle: Solitary; not a honeybee, not a bumblebee. Each female builds and defends her own nest.

- Signature habit: Nests inside active arboreal termite mounds; lines tunnels with tree resin carried and sculpted by those enormous jaws.

This is not a gentle garden bee scaled up. It is a forest engineer, equal parts mason and locksmith.

Strange/camouflage: housemates with termites

Why live in a fortress full of insects that bite? Three reasons:

- Security by stigma. Almost nothing raids a live termite nest; the scent and soldier patrols deter intruders.

- Microclimate. The carton walls regulate temperature and humidity—perfect for brood development in a climate of deluge and drought.

- Engineering synergy. The bee bores side galleries off the termites’ main routes, then varnishes them with sticky resin. Termites tend to avoid the resin—part chemical signal, part physical barrier.

The result is a nest that behaves like a safe-deposit box: tough, dry, and odor-insulated.

Anatomy of a builder

- Mandibles: Oversized, toothed, and backed by huge adductor muscles; they cut bark, scrape resin, and plane fibers smooth.

- Tarsal brushes: Hairy pads that mop resin and spread it like lacquer along cell walls.

- Thorax & wings: Built for short, powerful flights carrying payloads of sap and fibers; the buzz is low-pitched, more beetle than bee.

- Scopa (pollen-carrying hairs): On the abdomen (a megachilid hallmark), not the legs; the bee ends up dusted like a miner at shift change.

Majestic photography + storytelling: how to frame a living relic

- Find the address: Mature trees with bulging termite nests 2–15 m above ground; edges where sunlight stripes the trunk.

- Wait for the lacquer run: Females return with amber drops of resin that flash in backlight.

- Behavioral cues: A slow, door-check hover before landing; brief clacks from inside as mandibles test or reshape the portal.

- Ethics: Zero drilling, zero probing, zero bait. Keep distance; no flash bursts; never block the entrance. A stressed female may abandon an unfinished nest.

Survival battle: two empires in a tree

The bee must negotiate with termites every day. Too little resin and soldiers breach the gallery; too much disturbance and the colony moves deeper, collapsing the bee’s architecture. She also outflies predators—kingfishers, robber flies, lizards—while hauling literal glue. On rain days, resin stays viscous; on drought days, it skins over fast. The female’s calendar is a chemistry schedule, synced to sap flows and heat.

Brood cells are provisioned with a pollen–nectar loaf, topped with a single egg. After sealing, the bee becomes a guard and contractor, patrolling the entrance, touch-testing resin, and adding fresh coats until the resin cures like varnish.

What you didn’t know (and will remember)

- Largest bee ≠ colony giant. It’s a loner; one female is the queen, workers, and security team combined.

- Resin choice matters. She selects tree saps with antifungal and antibacterial chemistry—natural pharmaceuticals for brood.

- Termites aren’t passive. Soldiers test the bee’s barrier; a failed resin job means ongoing skirmishes at the interface.

- Tool-like mandibles. The bee saws resin ribbons and peens them into seams; watch for tiny, regular scrape marks around the entrance.

- Nest fidelity. Females often renovate old galleries, reading past resin like a blueprint.

- Sound signature. The entry buzz is a low thrum unlike the higher pitch of honeybees—locals can tell it by ear.

- Short flight range. Big body, heavy loads: she likely forages close; clear the nearest trees and you starve the nest.

- Male strategy. Males cruise routes between resin trees and nests, intercepting females mid-air—a sky of patrols rather than a flower patch hangout.

- Genetic risk. Patchy habitat means islands of kin; inbreeding looms if forests shrink further.

- Collectors are a threat. A single nest can be destroyed for a specimen; demand makes rarity dangerous.

Symbolism, culture, mythology

In the Moluccas, people talk about forest honey as a season, not a product. Megachile pluto is not a honey maker, but it’s become a modern emblem for the idea that forest value isn’t only timber: it’s pollination, resin, termites that aerate soil, and a bee that turns sap into architecture. As a story, it’s perfect for a generation re-learning that small engineers hold big systems together.

Field guide: where rare becomes possible (without giving away pins)

- Biome: Lowland to hill mixed forest; old trees with arboreal termite nests.

- Season & time: Dry breaks after rain; mornings when resin flows and termites are active.

- Signs: Fresh, varnished entrance on the side of a termite nest; resin smears on nearby bark; that unmistakable deep buzz.

- Etiquette: Work with local guides; never cut nests; keep coordinates off public posts.

Emotional rescue: the confiscated case

Customs opened a suitcase and found a glass-topped box: one female, pinned; one nest, shattered. A local NGO took custody, worked with officials to prosecute, and turned the exhibit into a traveling lesson shown in schools: why this bee matters, why a display case is a grave, and how tourists and buyers can say no. This is rescue redefined—not of one insect, but of future bees spared by ending a market.

Threats: the modern ledger

- Forest loss & logging roads: Remove resin trees, fragment bee–termite neighborhoods, and open poacher lanes.

- Specimen trade: High-priced demand for the “world’s largest bee” incentivizes nest destruction.

- Fire & drought: Kill resin sources; harden nest walls until they crack.

- Termite decline: Pesticides and tree removal reduce host colonies, erasing the bee’s housing stock.

What works (practical, proven)

- Keep old trees standing. Protect nest-bearing trees and a ring of resin sources around them.

- Community forestry & guardians. Pay locals to monitor termite nests, report bee activity, and flag illegal collecting.

- No-trade campaigns. Public pledges from collectors, curio shops, and online platforms: no buying, no selling.

- Micro-reserves. Small, legal “bee–termite sanctuaries” around known clusters—faster to implement than vast parks.

- Quiet science. Camera poles and acoustic loggers rather than intrusive nest checks; blurred site data in publications.

- Agroforestry buffers. Resin-rich native trees (Callophylum, Dipterocarps) in community plots—food for people, glue for bees.

Climate realism: sap in a hotter century

Resin chemistry, termite activity, and brood survival sit on tight temperature and humidity tolerances. Shade belts, riparian buffers, and fire breaks aren’t luxuries; they’re life support for a bee whose home is a living thermostat.

Personal narrative + moral

When she returned with a bead of resin the color of whiskey, the female hovered inches from my lens port and evaluated me like a contractor checking a permit. Then she slid past, feet forward, and vanished into the lacquered door. The clack resumed, patient and precise. I realized that the rarest things are not always loud or large. Sometimes they are work—done quietly, correctly, again and again, until a forest is held together by glue you can’t see from the road.

Moral: Keep the old trees. Starve the trade. Pay the guardians. If we do the ordinary things well, the extraordinary will keep knocking from inside the wood.

Fast FAQ

Is Wallace’s giant bee dangerous?

No. It’s solitary and avoids conflict. Those mandibles are for resin, not for you.

Does it make honey?

No. Solitary bees provision each cell with pollen and nectar, not communal honey stores.

Can I see one?

Only with local permits and guides. Even then, think signs and sound, not handling or close nest work.

How can I help?

Support community forestry in the North Moluccas, avoid buying insect curios, and amplify no-trade messaging.

Closing

A forest can lose its tigers and still keep a rhythm if it keeps its engineers. Wallace’s giant bee is one of those: a builder with thunder in its wings and varnish on its hands. Protect its trees and termites, and the knock inside the wood will continue—one more reason for a child to look up at a bulging nest and believe the world still makes marvels.

Reply