Rare moment: when the sand learned to lie

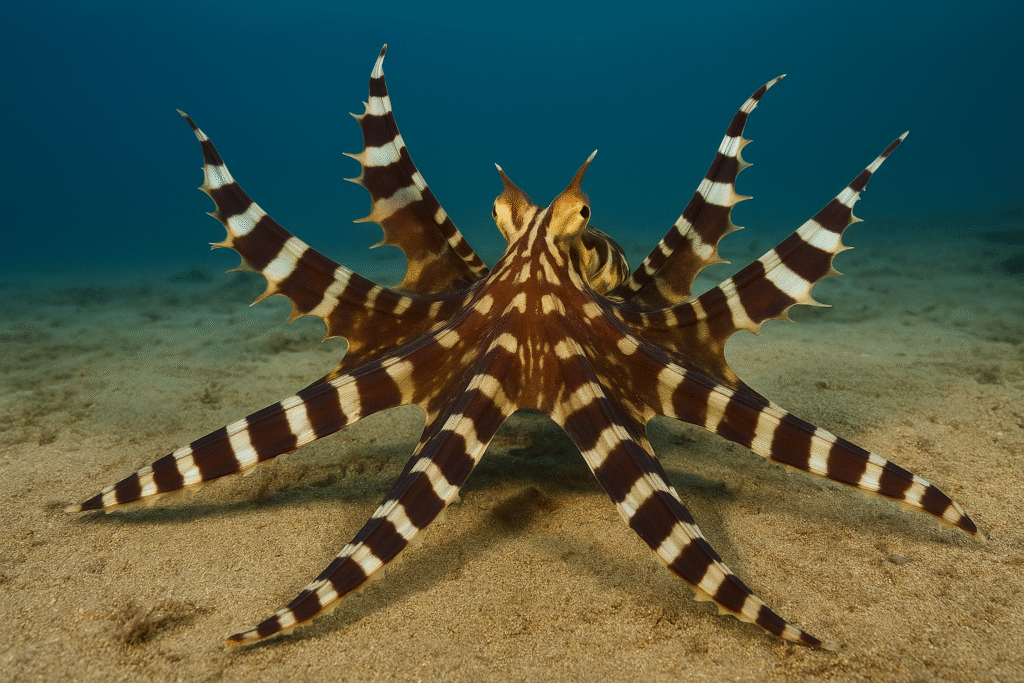

The tide was falling over a muck plain in North Sulawesi. Nothing moved but heat. Then the sand made a shadow, and the shadow became a fish—no, a lionfish, pectoral “spines” flared and toxic theater perfect. A dart of trevally came too close. In a heartbeat the “lionfish” flattened into a sole, ribboning across the bottom like a loose kite tail. Seconds later two “sea snakes” braided together and slipped into a burrow. There was only one animal the whole time: a mimic octopus, improvising identities as easily as we change expressions.

This is not special effects. It’s survival—shape, color, posture, and attitude composited into a moving lie.

What the mimic octopus is (and isn’t)

- Species: Thaumoctopus mimicus, described in 1998 from Indonesian waters.

- Range & habitat: Silty, open sand and seagrass beds of the Indo-Pacific (especially Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines). It favors places photographers call “muck”—low-relief sands rich in small prey.

- Build: Slender body (mantle to ~6–7 cm; arms to ~60 cm), high-contrast brown-white bands that it can switch on/off or smear into mottles within moments.

- Lifestyle: Diurnal hunter of crabs, shrimp, small fish; den-maker and sand-squirter; short-lived (typically 1–2 years), like most octopuses.

- Why it’s different: Others can camouflage. This species performs—adopting specific models of toxic or dangerous animals to deter predators.

Strange/camouflage: the repertoire of deception

The mimic octopus doesn’t just blend—it role-plays. Documented routines include:

- Sea snake – Raises six arms, tucks two, and waves two banded arms in S-curves while entering a burrow: a credible copy of the highly venomous Laticauda.

- Lionfish – Spreads arms like radiating spines, gliding in slow, regal pulses; predators read “painful” and keep distance.

- Flatfish – Compresses body, pairs arms into a trailing ribbon, and side-swims matching the undulation of soles/plaice.

- Jellyfish – Billows upward, arms draped like tentacles; useful in mid-water retreats.

- Crab duo – Walks on two arms while the others posture sideways: a bluff that seeds confusion among crab-eaters.

- Tube-worm or algae tuft – Curls and freezes, papillae raised, riding surge like unappetizing plant.

How it works (the quick science):

- Chromatophores (pigment sacs) expand/contract in milliseconds to paint the skin.

- Iridophores/leucophores scatter light for metallics and whites.

- Papillae raise and lower to change texture from glassy to gravelly.

- Neuromuscular “puppetry” in each arm lets posture copy the jointing of other animals.

- Context switching: It seems to choose a model that fits the local threat—sea snake for burrow raids by damselfish, flatfish in open sand, lionfish near reefs.

Survival battle: when performance buys lunch

A small lizardfish pins the octopus in the open. The octopus becomes flatfish, hugging the bottom to cut the strike angle; the predator hesitates—wrong outline—just long enough for the octopus to jet behind a clump. Now the actor flips roles: lionfish, spines “erect,” pacing past the lizardfish with theater-slow confidence. Predators hate uncertainty. The octopus eats that doubt and turns it into escape distance.

When hunting, the mimic plays a different game—deception for offense. It will ghost as debris until a shrimp peeks, then shoot an arm like a net and herd the prey into its mouth. If a crab flees to a hole, the octopus plugs entrances with stones (tool use) and flushes the crab out with a jet of water. Intelligence here is measured not in tests but tactics.

Emotional animal rescue: a tidepool return

Low tide, searing noon. A juvenile mimic octopus, marooned in a hot puddle no deeper than a hand. The guide’s first instinct was to scoop; we didn’t. Octopuses stress easily and their skin burns on dry hands. We floated a soft, water-filled tub, slipped it in, and let the animal swim by choice. In shade it revived, color returning from dull beige to clean bands. At the nearest channel we submerged the tub and waited; when the water pulsed cool, the octopus jetted free, settled, and ghosted into sand.

Rescue checklist (ethical, minimal):

- Keep the animal submerged; never handle dry.

- Use a smooth container with no snags.

- Move short distance to continuous water; do not relocate miles.

- No souvenirs (no arm tips, no photos that require prodding).

- If you see many strandings, note tide/coordinates and tell local rangers—site design may need fixing.

Majestic photography + storytelling: how to shoot a shapeshifter

- Find the stage: edges of sand tongues near current seams, 3–15 m deep.

- Approach low and slow: exhale fully, fin with ankles; let the octopus decide to continue acting.

- Wait for the switch: the moment between identities—the morph—is the magic frame.

- Lens & settings: 60–100 mm macro on crop; 1/160–1/200s to hold posture; dial strobe to preserve band contrast.

- Behavior before bokeh: if the animal buries fully, back off; that’s a “no.”

Symbolism, culture, mythology

Across the Indo-Pacific, octopuses sit at the crossroads of craft and mystery. Polynesian stories cast the octopus as a demiurge’s rival, builder of the world’s last island. Japanese folklore offers the Akkorokamui, a giant cephalopod both feared and revered. In coastal Sulawesi, elders read octopus tides as calendars for gleaning. The mimic octopus adds a modern parable: survival by reading the room, by learning predators’ fears and bending them back.

What you didn’t know about octopuses (and why it matters)

- Three hearts, blue blood. Copper-based hemocyanin works better in cold, low-oxygen water—but makes them heat-sensitive.

- Distributed brains. Two-thirds of neurons sit in the arms; each arm can problem-solve locally.

- Skin can “see.” Light-sensitive proteins in the skin help match backgrounds even without eye contact.

- RNA editing. Octopuses tweak gene messages on the fly, trading speed for neural flexibility.

- Tool use. Coconut and shell armor suits—they carry and assemble shelters.

- Escape artists. No bones; any gap wider than a beak is a door.

- Short lives, big smarts. Most species live 1–2 years; smarts are compressed into fast learning.

- Taste by touch. Suction cups sample chemicals; an arm can “decide” a food is good or bad before the mouth.

- Ethical frontier. Many countries now include cephalopods in animal welfare frameworks—their cognition demands better handling.

- Climate vulnerability. Warming and deoxygenation tax blue-blood circulation; coastal pollution batters nurseries.

Field guide: where and when to see one (responsibly)

- Hotspots: Lembeh Strait & Bunaken (Indonesia), Anilao (Philippines), Mabul (Malaysia).

- Season & time: Post-monsoon clear spells; mid-tide when currents stir life but don’t rip.

- Signs: Paired row of sand “volcanoes” (den + dump), sudden moving “weed,” small fish hovering like camp followers.

- Code of conduct: One dive team at a time; no sticks, no pokes; minimum flash bursts; end the session if the animal inflates mantle or goes pale for more than a minute.

Conservation: the costs of a clever life in a hard century

- Habitat loss: Coastal reclamation and trawl scars erase the featureless plains this species needs—emptiness is its habitat.

- Bycatch: Small trawls and beach seines take octopuses silently; few records, many losses.

- Pollution: Microplastics and oil bind to silts; octopus dens sit in the sink of watersheds.

- Heat & hypoxia: Blue blood carries less oxygen in warmth; shallow bays hit nighttime low-oxygen first.

What helps: protect “boring” sand flats; enforce no-trawl corridors inside reef shelves; upgrade sewage so silts don’t suffocate nurseries; back community-run marine areas that keep gleaning sustainable and give guides income for leaving animals undisturbed.

Personal narrative + moral

When the octopus finally settled, only two eye-horns peeped from sand like punctuation marks. A goatfish nosed past; the sand blinked and the “sea snake” flowed out again. I realized I was staring at an animal that survives by reading minds—by modeling the fear of something else and rehearsing it better than the original. On a planet changing this fast, intelligence isn’t just memory; it’s adaptation at the speed of a heartbeat. Our job is simple in concept and hard in practice: leave enough stage for the actors to keep performing.

Fast FAQ

Is the mimic octopus dangerous?

No. The mimic’s “venom” is theater. It pretends to be venomous animals to avoid being eaten.

Can it really choose which animal to mimic?

Evidence suggests context-dependent choices: it tends to pick models that live locally and deter the predator currently present.

How big does it get?

Mantle roughly 6–7 cm; arm span up to ~60 cm. It looks larger when performing.

Are they kept in aquariums?

Rarely and briefly. Short lifespans, high stress, and complex needs make this a poor candidate for display.

What’s the best way to help?

Support coastal habitat protection, sustainable fisheries, and dive operators who follow no-harass codes. Choose seafood with bycatch-safe methods.

A wave drags a thin veil across the bottom and the actor is gone, nothing left but neat ripples and two holes that look like coincidence. The mimic octopus is a reminder that the sea isn’t only vast; it’s inventive. If we defend the quiet places—the ordinary sands, the channels that look like nothing at all—then the great performances continue. And somewhere on a falling tide, a piece of living grammar will turn fear into form, and form into survival.

Reply