At first glance it’s a twig with a pulse. The southern two-striped walkingstick (Anisomorpha buprestoides) spends most days frozen against stems and saplings, a sliver of stillness in humid air. But press too close—brush it with a finger, a snout, a curious lens—and the twig becomes a device: twin ports just behind the head snap open and a milky jet arcs through space with startling accuracy. No flames, no noise—just chemistry delivered to the most persuasive address on a predator’s body: the eyes.

This is not the spectacle of a Bombardier beetle’s boiling spray. It’s a different philosophy of defense: cold, immediate, and aimed. Think of it as nature’s pepper spray—metered, directional, and memorable.

Blueprint of a “twig”

Walkingsticks (order Phasmatodea) are built for disappearing. Long legs stretch the body into geometry; antennae sweep like second thoughts. The cuticle is matte, the colors leaf-litter dull. Camouflage is the first line of defense. The two-striped walkingstick adds a second: a pair of thoracic glands that open on the sides of the pronotum, just behind the head. Each gland ends in a tiny nozzle. The hardware is bilateral for a reason: it lets the insect choose which side to fire—or fire both at once.

Inside, the reservoirs are finite. They hold a viscous, terpene-rich secretion under modest internal pressure, ready to vent the moment the nervous system decides stealth has failed. There is no warm-up. One instant you see a stick. The next, a white thread stitches the air.

Chemistry with bite, not heat

The walkingstick’s secretion is a blend of reactive monoterpene dialdehydes—most notably anisomorphal, alongside close relatives such as dolichodial and peruphasmal. These molecules don’t scald; they irritate. They bind and react with proteins on moist membranes and nerve endings, producing a burning, tearing pain that dominates the senses for minutes to hours. The blend is not fixed. Populations differ; nymphs and adults may favor slightly different ratios. That variability is a theme across insect chemistry: evolution tunes recipes to local predators and plants, and to the energy budgets of the insects themselves.

Because the secretion is chemically aggressive, a little goes a long way. Direct hits to eyes cause immediate blinking, tearing, and retreat. Mouthparts and nostrils are nearly as sensitive. Skin seldom suffers more than an itchy patch—unless you rub it into your eyelids.

Ballistics and aim

Range is the measure that surprises people. In good condition, a large female can score the face of a would-be harasser at arm’s length. The jet is not a dribble; it’s a coherent stream for the first slice of its flight, then a widening mist that still carries enough punch to change minds.

Aim is the real marvel. The insect does not have to twist its whole body. With subtle thoracic movements it points the relevant nozzle like a tiny turret. Tap from the right and the right port answers. Press from above and both fire in a crossing spray. This precision, paired with bilateral plumbing, keeps consumption low and success high. It is a defense measured in milliliters but paid back in meters of distance.

The defensive playbook

If you could watch a walkingstick’s threat-response in slow motion, it would read like a protocol:

- Freeze. Camouflage gets first turn; most threats pass by if nothing moves.

- Reposition. A slow sidestep to place a stem or leaf between insect and intruder.

- Warn. A slight lift of the thorax, a subtle canting of the head—tiny signals that a line has been reached.

- Fire. One burst, then silence. If the intruder persists, another. No wasted flailing, no spraying the wind.

Because reservoirs take days to recharge fully, restraint is part of the design. The walkingstick fires when it must, not because it can. Economists would call it optimal deterrence. Field naturalists simply call it effective.

Life beyond the jet

Strip away the drama and you find a slow herbivore with an intricate domestic life. The species frequents shrubby edges, young oaks and pines, palmettos, and ornamentals in warm regions of the southeastern United States. Dusk is commute hour; nights are for feeding.

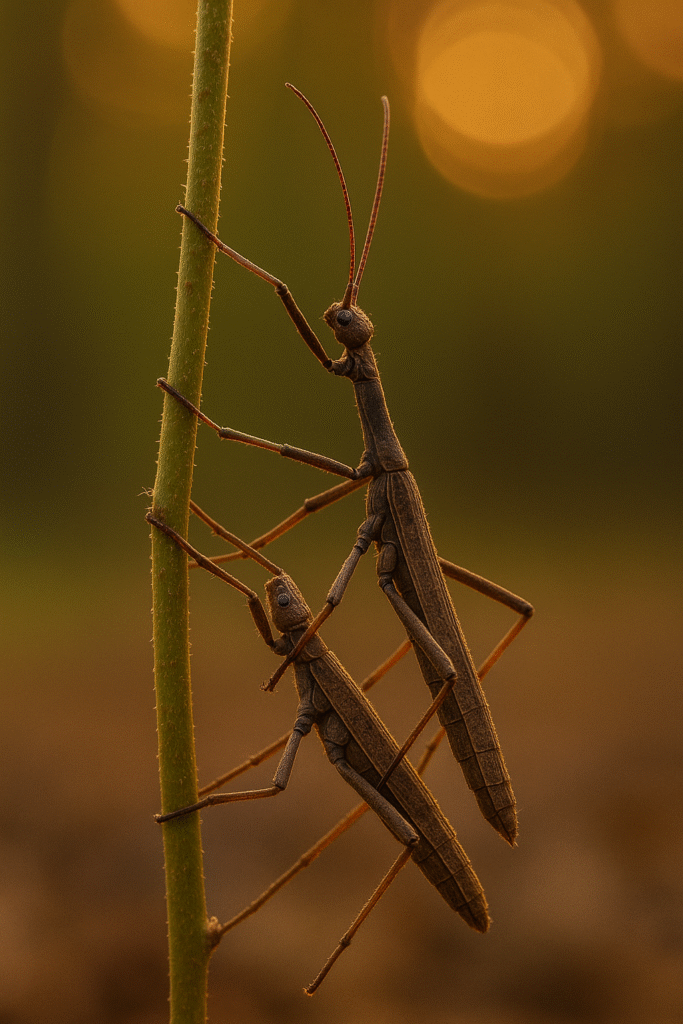

The sight most people remember is the rider pair: a slender male perched lengthwise atop a broader female. Pairs may remain aligned for hours or days as they travel, feed, and rest. The pose is not only about mating opportunities; it is also a defensive alliance. Two sets of glands, four nozzles, twice the warning signals. Eggs are laid in soil or leaf litter; nymphs hatch as miniature twigs, growing through molts with the same faith in stillness until their chemistry matures.

Predator case files

- Birds: Quick learners. After one mist to the nictitating membranes, many abandon the odd “twig” for less opinionated prey.

- Lizards: Close enough to grab, close enough to regret it. A head shake, an urgent blink, a retreat to the shade.

- Spiders: Ambushes sometimes succeed, but misted mouthparts slow handling and the prize is often released.

- Mammals (including pets): A nose is a generous target. Dogs add a cautionary footnote to many a neighborhood encounter.

The point is not punishment; it is memory. A single clean hit can create a predator that recognizes and refuses the species thereafter. Deterrence reshapes communities as surely as predation.

Variation and evolution

Chemical defense in insects rarely appears all at once. Across the walkingstick family you find a spectrum: species that rely almost entirely on camouflage; others that ooze un-aimed secretions; and a few, like Anisomorpha, that perfected directional jets. It’s easy to tell a tidy story: first make something nasty, then store it better, then point it. Whether or not evolution always follows that sequence, the logic is clear—separate storage from release, meter output, and add steering. Stepwise gains accumulate into a system that looks, in hindsight, inevitable.

Convergence underscores the lesson. African Anthia ground beetles shoot formic acid; nasute termite soldiers deploy terpene glue from a head-mounted fontanelle; “false bombardier” beetles deliver their own acid mix. Different lineages, parallel solutions: aimed chemistry beats brute force when the goal is not to kill, but to convince.

What engineers notice

- Bilateral nozzles provide left/right steering with minimal motion—useful for micro-sprayers where moving the whole chassis is expensive.

- On-demand dosing conserves a scarce resource, echoing design choices in medical nebulizers and agricultural micro-emitters.

- Benign storage, reactive outcome: keep components stable until the moment of need; deliver potency at the point of contact.

- User experience (from the predator’s perspective): fast onset, strong sensory feedback, short memory window—precisely the profile of an ideal deterrent.

Ethics in a twig

It is tempting to read grand ideas into small lives, but some metaphors earn their keep. The walkingstick’s defense is boundary made visible. It asserts a line—clear, precise, reversible—and then returns to stillness. In a world that often confuses volume with power, here is an animal that wins by saying “enough” quietly and exactly.

Field guide and first-aid notes

- How to see one: Walk slowly along shrub lines at shoulder height in late afternoon or evening. Look for “twigs” that don’t quite align with the plant’s grammar.

- Respect the range: Keep eyes and faces at least half a meter away. If the insect pivots to face you and lifts slightly, you’re in the splash zone.

- If you’re sprayed: Do not rub. Flush eyes copiously with clean water or saline for several minutes. Remove contact lenses after the first rinse. Mild skin exposures usually need only soap and water. Seek medical care if pain persists.

A final image

Rain threatens, and a south wind lifts the leaves. On a sapling at the edge of a trail, a brown line with legs becomes two lines as a male climbs the back of a female. They still themselves until the breeze and the world forget them. Somewhere nearby a wren searches for something smaller, simpler. The walkingsticks ask for nothing more than distance—and have found, in a thimble of chemistry and a pair of nozzles, a way to keep it.

Power, kept. Boundary, held. The twig, still a twig—unless you insist.

Reply