Prologue: a river that runs through stone

Follow the Adriatic inland and the rivers begin to misbehave. They slip into sinkholes, vanish beneath pastures, and reappear as cold blue eyes in the limestone. The land is riddled with chambers and tunnels, a drowned cathedral carved by rain and time. In this underworld lives a creature shaped by darkness itself: the olm, also called proteus or the “human fish.” Pale as unlit marble, crowned with feathery gills and built for a lifetime without sunlight, the olm is Europe’s only truly subterranean vertebrate. It is not a tourist in the cave realm but a citizen, born, fed, and bred in water that rarely meets the day.

1) What the olm is—and isn’t

The olm is an amphibian, a salamander by lineage, but it breaks nearly every rule the typical frog-or-salamander picture suggests.

- Body plan: elongated and sinuous, usually 25–30 centimeters long, with tiny limbs and delicate toes.

- Gills forever: unlike most amphibians, it retains external, feathery gills throughout life. This is neoteny—the animal keeps larval traits even as it matures sexually.

- Eyes reduced: buried beneath translucent skin, the eyes register changes in light but do not form images.

- Skin without pigment: the common form is ivory or faintly pink, the blood shining gently through; a rarer, pigmented “black olm” exists in a tiny corner of its range.

- Mouth and diet: a small, soft-edged mouth takes tiny invertebrates—crustaceans, snails, insect larvae—whole. There is no drama here, only precision.

The overall impression is of something unfinished, but that is an illusion: the olm’s “simplicity” is engineered, not primitive. In a world with almost no light, the body stops wasting resources on eyesight and color. Energy is moved to what matters.

2) Where it lives: the Dinaric Karst

The olm’s address is the Dinaric Karst, a vast belt of fractured limestone stretching from northeastern Italy through Slovenia and Croatia to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Karst is a geology of absence: rock dissolved by acidic rain, leaving voids, shafts, galleries, and siphons. Rivers slip underground, flow through black corridors, then return to the surface as springs. The olm inhabits the saturated threads of this labyrinth—permanently flooded caves and aquifers where water is cold, oxygen low, currents patient, and seasons muted.

Because the habitat is three-dimensional and hidden, mapping the species’ distribution is notoriously difficult. Confirmed sites cluster around significant cave systems and their outflow springs, but there are likely more populations threaded through the rock, connected by corridors too narrow for people and too complex for simple surveys.

3) The physics of a life without light

When you subtract light, vision is no longer the cheapest way to make sense of the world. The olm compensates with a fused sensorium—several senses overlapping to recover the missing information.

- Chemoreception: smell and taste sharpen into a single instrument. Olms can detect faint chemical trails in moving water, separating the background soup of minerals and organics to find food or mates.

- Mechanoreception: skin and lateral-line organs pick up minute vibrations and water movements. A drifting amphipod becomes a tremor, a map in ripples.

- Electroreception: specialized receptors can sense weak direct-current fields produced by living tissue. In darkness, life quite literally “glows” electrically.

- Light awareness without sight: even with skin-covered eyes, the body registers changes in light intensity through extra-ocular photoreceptors. Day or night at the surface still matters; floods tend to follow storms.

None of these senses alone replaces vision; together they allow probabilistic living—a strategy tuned to the slow, sparse, low-energy world of caves.

4) Time slowed to a whisper: longevity and starvation tolerance

The olm bends our expectations for how small vertebrates age and feed.

- Long lives: average adult lifespans approach seven decades, with upper limits around a century.

- Rare meals: in controlled conditions, individuals have endured years without food by lowering activity, reallocating internal resources, and making almost no mistakes.

- Movement as a choice, not a habit: mark–recapture studies show extreme site fidelity; an olm may occupy a single crevice or pool for years. When the habitat is hostile to movement and unpredictable in reward, sitting skillfully is superior to roaming.

This is a mathematics of scarcity: moving burns calories, risks predators and floods, and offers little guarantee of a better patch. The olm’s genius is not in doing more; it is in doing less, perfectly.

5) Life history in the dark

Neoteny defines the olm’s entire career. By never completing metamorphosis, it remains fully aquatic, breathing through its external gills and skin. The thyroid gland is functional; what is unusual is how tissues respond—resisting the hormone-driven cascade that would ordinarily remodel a larva into a land-walking adult.

Reproduction is infrequent and cautious. Females lay small clutches on protected surfaces—rock ledges, hidden crevices—where oxygen flow is steady but gentle. Incubation takes months; hatchlings emerge as miniature adults with their own tiny gills. Survival in the wild appears low and episodic, tied to subtle shifts in water chemistry, temperature, and flow. In near-natural conditions inside tourist-accessible caves that double as research sites, patient care has produced rare bursts of successful hatching, offering a window into natural timings and tolerances.

6) Behavior: the art of minimalism

Olms are master minimalists. Their baseline is stillness, interrupted by brief decisions: a lunge for drifting prey, a glide to fresher current, a retreat from silt. They occupy micro-territories that often look identical to our eyes but differ in important ways—slightly higher oxygen, cleaner substrate, or a steady trickle of invertebrates from an upstream crack. Courtship, when it happens, is understated: a choreography of approach, chemical signaling, and precise placement of eggs. The entire repertoire is quiet.

7) Culture and myth: the baby dragon

Floods occasionally flush olms from their caves into surface streams. Medieval villagers who found pale, eel-like animals with red gill fans called them dragon young. The nickname stuck. In modern Slovenia the olm serves as a cultural shorthand for the country’s subterranean identity: rivers that vanish, mountains that breathe, and animals that seem to come from legend. Public affection matters. It turns groundwater protection from an engineer’s checkbox into a source of shared pride.

8) Status and threats

The olm’s greatest vulnerability is water quality. Caves and aquifers are plumbing, not ponds, and whatever happens on the surface arrives underground rapidly—fertilizer runoff, septic leaks, industrial effluent, road salt, even careless illumination that spurs algae growth where there was none. The species is widely recognized as threatened, with concerns focused on habitat degradation rather than direct exploitation.

Two forms complicate conservation. The common form is the pale olm. A rarer, pigmented “black olm” is restricted to a tiny area; genetically close to its pale cousin yet ecologically and geographically unique, it functions as a separate conservation unit. When a lineage occupies a postage stamp of land, a single polluted pulse can write an ending.

Tourism is a double-edged torch. When managed carefully—lights positioned to limit algae, temperatures stable, humidity and noise controlled—visitor income can finance research and protection. When unmanaged, footfall and lighting degrade precisely the micro-habitats that sustain eggs and juveniles.

Climate change adds a slow pressure. Altered rainfall patterns shift the timing and intensity of floods, changing oxygen and silt loads in underground streams. Caves that were once stable can become volatile.

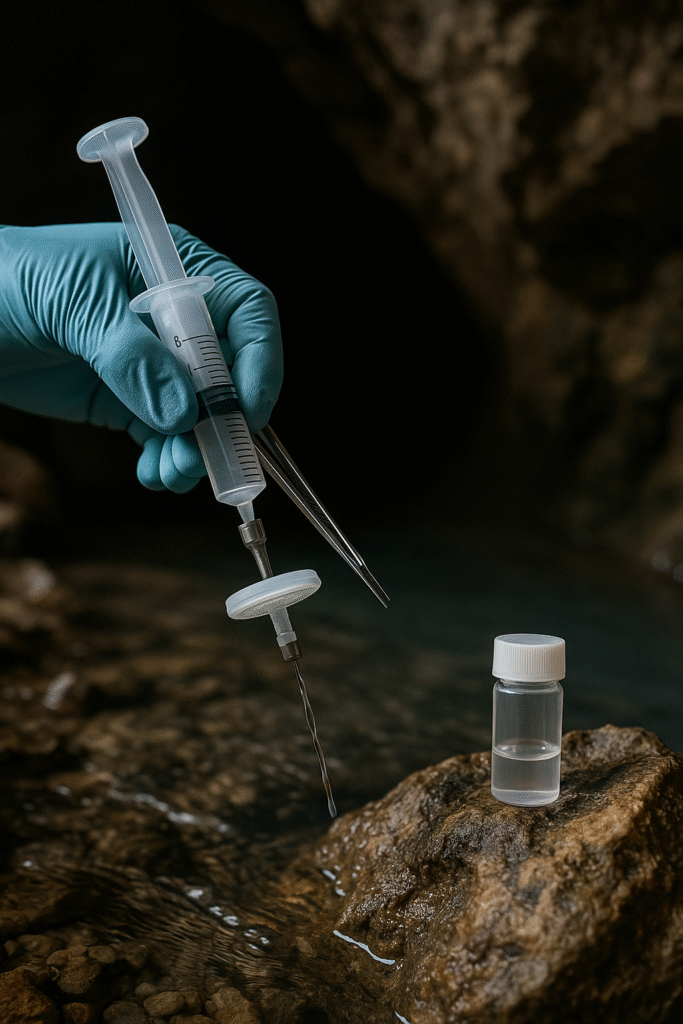

9) How scientists “see” an invisible animal

Surveying subterranean life is a lesson in humility. Divers and speleobiologists are limited by human need for air and warmth; cameras often biofoul in days. The most powerful modern tool is environmental DNA (eDNA): filtering cave water for sloughed cells that carry the animal’s genetic signature. With eDNA, researchers can map presence across hundreds of springs and inflows without ever laying eyes on a salamander. Once a spring or passage tests positive, short, carefully placed camera deployments or discreet visual checks can confirm animals while keeping disturbance minimal.

This is cave biology as forensic science. You assemble the case molecule by molecule, then ask for a photograph only when the odds justify the intrusion.

10) Conservation that actually works

Protecting an underground species demands thinking like water. Effective programs share the same backbone:

- Guard the catchment, not just the cave. Protecting a show cave means little if the farms and factories above the recharge area leak nutrients and toxins. Land-use plans must treat sinkholes, losing streams, and swallow holes as critical habitat inputs.

- Upgrade sanitation and runoff control. Septic systems, wastewater plants, and storm drains should be engineered with karst in mind—tight, monitored, and conservative.

- Monitor with eDNA, seasonally and forever. Regular sampling turns anecdotes into data, revealing trends and allowing rapid response when sites go from positive to silent.

- Design tourism around biology. Use narrow-spectrum, low-intensity lighting, manage numbers and paths, and let biologists—not marketing—set the thresholds.

- Safeguard micro-lineages. If a population is geographically tiny, treat it like an island species: tighter water-quality triggers, local stewardship, and genetic banking where appropriate.

- Invest in local pride. Cavers, farmers, and municipal engineers are the front line. When they see the olm as a neighbor rather than a curiosity, protection becomes ordinary work, not a special project.

The metric of success is not a sudden boom of young; it is decades without funerals.

11) Frontiers of science

The olm still puzzles the disciplines that study it.

- Aging biology: How does a small vertebrate live nearly a century without the catastrophes that accompany long life elsewhere? The answer likely lies in repair systems and damage avoidance rather than a sluggish metabolism alone.

- Developmental tweaks: Neoteny is common in salamanders, but the olm’s refusal to metamorphose is unusually complete. Understanding the gene networks and tissue responses involved could illuminate how bodies negotiate change.

- Population connectivity: The species’ range is a net of underground rivers. Which localities truly exchange individuals and genes, and which are isolated aquaria? eDNA paints the outlines; long-term studies will shade them in.

- Energetics of darkness: Food webs in caves are brown—driven by organic matter washed in from the surface rather than photosynthesis on site. Modeling carrying capacity under such frugality is still an art.

12) Field craft and ethics

Underground ecosystems are easy to love and easy to break. Good practice is simple and strict.

- No pin-drops. Share generalized locations, not GPS coordinates.

- Minimal light, minimal time. In eggs and larval zones, even small changes in light and temperature can tip the balance.

- Leave nothing. No food, no bait, no foreign microbes; disinfect gear as if every cave is an operating room.

- Tell the story of water. Every piece of outreach should trace a line from a hillside septic tank to a cave pool where gills flicker.

13) Practical guide for readers and editors

Common names: Olm, proteus, “human fish.”

Scientific name: Proteus anguinus.

Family: Proteidae (related to North America’s mudpuppies, though far removed in time and ecology).

Range: Subterranean waters of the Dinaric Karst from northeastern Italy through Slovenia and Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Habitat: Permanently flooded caves, siphons, and aquifers; cold, oxygen-poor, stable environments.

Size: Usually 25–30 cm; slender, eel-like.

Color: Ivory to faint pink in the common form; fully pigmented in the rare “black olm.”

Senses: Heightened smell, taste, and mechanoreception; electroreception; light sensitivity through skin.

Diet: Tiny aquatic invertebrates; opportunistic scavenging.

Lifespan: Average adult life measured in many decades; maxima around a century.

Reproduction: Infrequent; small clutches; long incubation; slow juvenile growth.

Threats: Groundwater pollution, habitat fragmentation, unmanaged tourism, climate-driven hydrological change.

Conservation priorities: Catchment protection, sanitation upgrades, eDNA surveillance, carefully managed public access, micro-lineage safeguards.

14) Why the olm matters

There are charismatic megafauna that command attention with size, speed, or spectacle. The olm earns attention with absence. It shows us that the planet is larger from the inside than we imagine. It teaches a harsh lesson about hydrology: that caves are not separate from farms, roads, and towns but are downstream of all of them. And it offers an ecological manifesto disguised as a salamander—patience, frugality, and precision can outperform force.

Save the olm and you have not only kept a rare amphibian from vanishing. You have protected the aquifers that feed villages, the springs that anchor valleys, and the quiet contract between rock and rain that keeps entire regions alive.

15) Closing: listening to stone

Stand at a karst spring after a storm. The hillside exhales. Cold water, metallic and clean, issues from an opening that looks like a myth. Somewhere behind that mouth, in vaults where no map is honest and no noon exists, a pale animal waits. It has waited for decades, through hunger and flood, through winters that do not change the water by a degree. When a small crustacean tumbles past, the olm will move with the speed of a thought and then resume its stillness. It does not need our applause. It needs our discipline. If we keep the water worthy of gills, the ghost will remain in the stone, not as legend, but as life.

Reply