Prologue: a shadow under a single bush

On a volcanic blade called Ball’s Pyramid—an obsidian spear rising from the Tasman Sea—climbers once found a shrub clinging to a ledge and, beneath it, a handful of glossy, heavy-bodied insects the size of cigars. They were supposed to be extinct. Islanders called them tree lobsters for their heft and armor. Science called them Lord Howe Island stick insects and had already written the obituary. Yet there they were in 2001, alive in twos and threes, hiding in the dripline of a lone tea tree where wind could not reach. The rediscovery felt less like a miracle than a correction: nature had been working offstage the whole time.

1) Identity: what the “tree lobster” really is

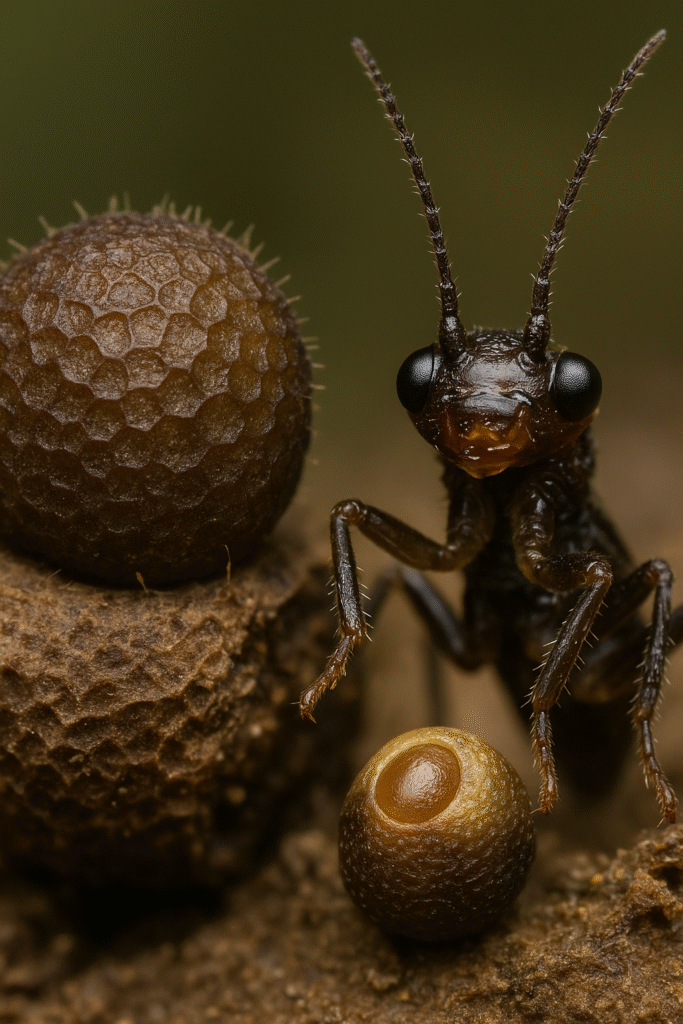

- Taxonomy: Order Phasmatodea (stick insects); species Dryococelus australis.

- Look & size: Adults are massive for a stick insect—up to 15–20 cm long, thick-bodied, dark mahogany to black with a lacquered sheen. The legs carry blunt spines; the abdomen of females ends in a stout, curved ovipositor.

- Sexes: Males are slimmer with longer legs and often keep a companion grip on females; females are heavier, the engineers of the next generation.

- Tempo: Nocturnal. By day, they wedge into crevices or cluster in sheltered cavities; by night, they climb and feed.

- Name story: “Tree lobster” comes from islanders who saw a big, jointed, armor-like insect that moved with deliberate strength. It’s an apt metaphor; this phasmid isn’t a delicate twig—it’s a walking branch with weight.

2) Extinction on paper: rats, ships, and silence

In 1918 a supply ship wrecked on Lord Howe Island. Black rats made landfall and multiplied. Within a couple of years, the stick insect—once so common locals used them as fishing bait—vanished. For most of the 20th century the species was considered gone. Then the rumor began: climbers on Ball’s Pyramid, a sheer rock 23 km southeast of Lord Howe, reported droppings, gnaw marks, and later, live insects beneath a storm-sheltered tea tree. A relict population had persisted on a knife-edge of rock—rats never reached the Pyramid, and that was enough.

3) Biology in a cliff’s dictionary

Diet. In the wild the insects browse tough coastal shrubs—on Ball’s Pyramid, tea tree and other hardy plants; on Lord Howe, the historical menu was wider. In captivity they accept Melaleuca, paperbark, Lagarostrobos, and several island natives grown as feed.

Behavior. At night, adults move with slow power, gripping bark with padded tarsal “mitts.” Mated pairs often rest touching—keepers call them “pairing,” a loose but useful term: a male will sit astride or beside a female for hours, a behavior that may reduce lost mating opportunities in a sparse population.

Eggs. Females lay large, seed-like eggs (phasmid classic) and, unlike many stick insects that simply drop them, push them into soil with the ovipositor. In a stormy world, burial is insurance. Incubation is long—many months—spreading risk across seasons.

Nymphs. Hatchlings are smaller, paler, and more active than adults, often greenish-brown at first. They hide in tight crevices and ascend plants at night, molting through several instars to reach adult mass.

Lifespan. In managed care, adults may live over a year; the full egg-to-egg cycle commonly spans 18–24 months, depending on temperature and diet.

4) Why this stick insect is built like a tank

Phasmids usually win by pretending not to exist. Dryococelus plays a different game: armored stillness plus strength. On wind-scoured cliffs, a light twig-body would pinwheel into the sea. A heavy, rounded insect that can brace and grip survives gusts, salt, and scraping leaves. Even the glossy cuticle helps—shedding water, resisting abrasion, and slowing desiccation when ocean air turns knife-dry.

5) The rescue: from twelve insects to thousands

Following rediscovery, a genetic and demographic bottleneck stared conservationists in the face. Field teams carefully collected a breeding pair (later, a few more) to establish assurance colonies. Husbandry had to be invented: correct host plants, temperature bands, humidity, burrowing media for eggs, disease control. Within a decade, specialized breeding programs produced thousands of offspring—insurance populations at multiple zoos and institutions. Every clutch carried both promise and math: maximize genetic diversity from very few founders while scaling numbers for eventual return.

6) Erasing the villain: the rat eradication

No return was possible while rats remained on Lord Howe Island. After years of preparation and community debate, a comprehensive rodent eradication was implemented—stringent baiting, follow-up trapping, sniffer dogs, and multi-year monitoring. With rats suppressed to undetectable levels, the door cracked open. Habitat teams began pilot reintroductions in rat-free zones, paired with intensive monitoring—night surveys, egg searches, chew cards, acoustic and thermal checks, and eDNA in soil to catch the species’ molecular signature. The strategy is cautious by design: phase the return, learn fast, adjust.

Conservative truth: staged, limited releases have begun only where post-eradication monitoring supports safety; broader releases will follow data, not wishful thinking.

7) Genetics: living with a bottleneck

All modern stick insects descend from a tiny refuge population. That concentrates risk:

- Low allelic diversity can increase vulnerability to disease and reduce fertility.

- Inbreeding depression is a possibility across generations if lineages aren’t carefully managed.

Breeding programs therefore treat pairings like chess, not checkers—tracking pedigrees, rotating founders’ lines, avoiding pairings of close kin, and periodically sampling DNA to ensure diversity isn’t silently collapsing. Success is measured not just in numbers, but in heterozygosity retained.

8) Ecology on Lord Howe: the job it used to do

A large nocturnal browser changes plants differently from a bird or a beetle. The stick insect:

- Prunes tough shrubs, encouraging branching and light penetration.

- Moves nutrients from woody leaves into the litter as frass pellets that fungi and soil biota quickly process.

- Feeds night predators, from geckos to owls—restoring a nocturnal trophic link lost for a century.

Reintroducing Dryococelus is not cosmetic; it stitches back function into an island web.

9) Husbandry: the quiet craft behind a comeback

Successful breeding rests on details your eyes almost miss:

- Host plant quality—growing pesticide-free browse in controlled nurseries; leaves must be at the right age and toughness.

- Microclimate—stable temperatures and humidity with a nightly drop; strong airflow without drafts.

- Egg care—clean sand/soil blends, gentle moisture cycles, and long patience; eggs “rest” through seasons for staggered hatching.

- Biosecurity—footbaths, quarantines, and careful separation of lines; one pathogen could erase years of work.

Behind every triumphant press photo is a thousand hours of checking leaves, misting, sifting soil, and counting hatchlings with tweezers.

10) Fieldcraft for rewilding: how teams “see” a night that hides

- Rock crevice surveys under red light to reduce disturbance.

- Chew cards (corrugated bait strips) that record distinctive mandible marks.

- Thermal scopes to pick out warm bodies against cool stone at night.

- Soil eDNA around likely oviposition sites for early, non-invasive detection.

- Autonomous cameras at micro-refuges to watch activity without constant human presence.

The rule: detect more, intrude less.

11) Risks ahead and how to answer them

- Predator rebounds. As islands recover, native predators may rediscover a large, slow insect. Refuge microhabitats and phased releases spread risk.

- Plant shifts. Climate and storm regimes could alter host-plant performance; teams hedge by planting diverse browse patches.

- Human lapse. A single rat stowaway can undo years. Ports, freight, and visitor luggage stay under permanent biosecurity.

- Complacency. Success breeds sleep. Programs commit to decade-scale funding and independent audits.

12) Myths to retire—and truths to keep

- Myth: “It was a miracle under one bush.”

Truth: It was habitat physics + isolation + luck; a cliff did what a fence could not. - Myth: “Now that rats are gone, we can dump them back.”

Truth: Rewilding is staged—start small, test, expand—because failure at scale is permanent. - Myth: “Stick insects can reproduce without males, so genetics don’t matter.”

Truth: Parthenogenesis is not the plan; diversity is survival. Managed pairings matter.

13) Why this comeback matters beyond one insect

- Template value: The project is a playbook for other island invertebrates: find the refuge, solve the invader, scale husbandry, return function.

- Story power: A species declared extinct “returns” and makes conservation feel solvable, not abstract.

- Island integrity: Restoring an endemic’s role—pruning, nutrient flux, nocturnal biomass—improves resilience against storms and climate swings.

Save the tree lobster and you save more than a headline; you upgrade an island.

14) What success will look like (not a press release, a night walk)

You’ll climb a low ridge on Lord Howe with a ranger at dusk. Wind presses salt into your ears. In the red glow of a lamp, a dark shape moves like a careful hand along a paperbark. Another sits in a fissure, antennae tasting air that smells of tea tree and damp rock. The island sounds different when big insects are back—more rustle, more small snapping of leaves. In a sandy run beneath the shrubs, you kneel and sift; a single seed-like egg rolls against your fingertip. You cover it again. You can leave because the island can now continue without you.

15) Quick reference (for your editorial deck)

- Common name: Lord Howe Island stick insect, “tree lobster.”

- Scientific name: Dryococelus australis.

- Status: Once presumed extinct; now conservation dependent with robust assurance colonies; staged reintroductions underway following island rat eradication.

- Key threats: Invasive rodents, stochastic events in tiny wild populations, disease in captive lines, climate extremes.

- Core interventions: Rodent eradication, multi-site captive breeding, genetic management, phased releases, long-term monitoring and biosecurity.

16) Closing: a correction, not a miracle

The tree lobster did not come back to impress us. It came back because cliffs kept a corner of the world hard enough for it to continue, and because people decided to do the work—dirty, patient, unglamorous—to make room for its return. The species is not a relic; it is current. When it clamps those padded feet on bark and leans its weight into wind, the island regains a piece of itself.

A good conservation story is not magic. It is method + stubbornness + time. That’s how a rumor under a single bush becomes a population you can meet on a night walk—quiet, solid, and exactly the size it always was: the size of hope you can hold.

Reply