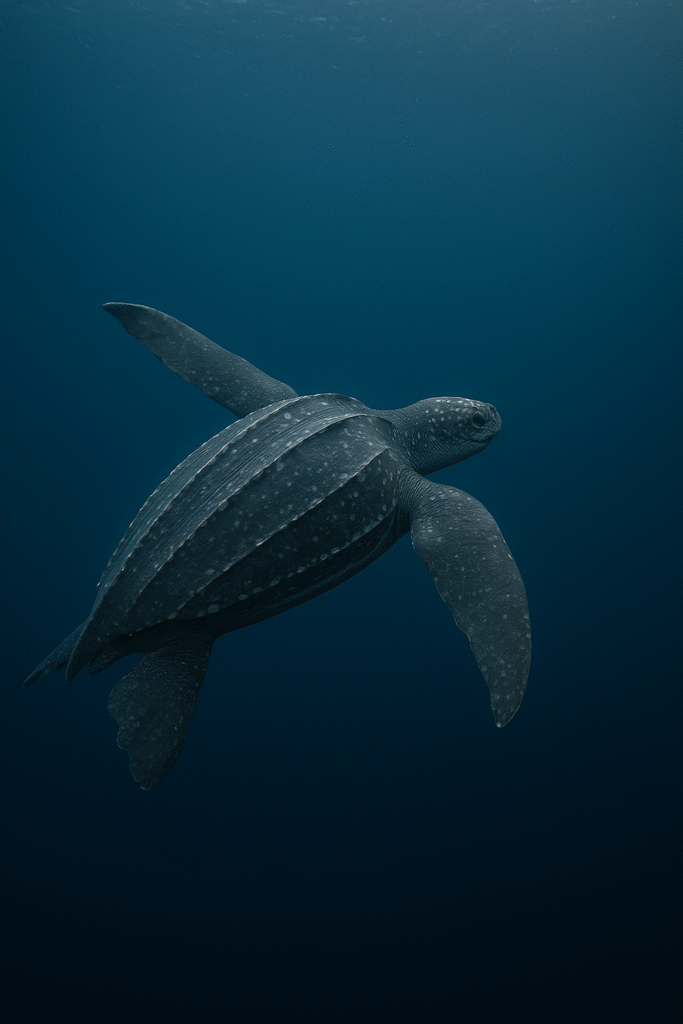

There are creatures whose lives unfold at a scale beyond human comprehension—creatures whose every migration is an odyssey, whose very survival seems to defy time. Among them is the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), the largest living turtle on Earth and the last of its kind.

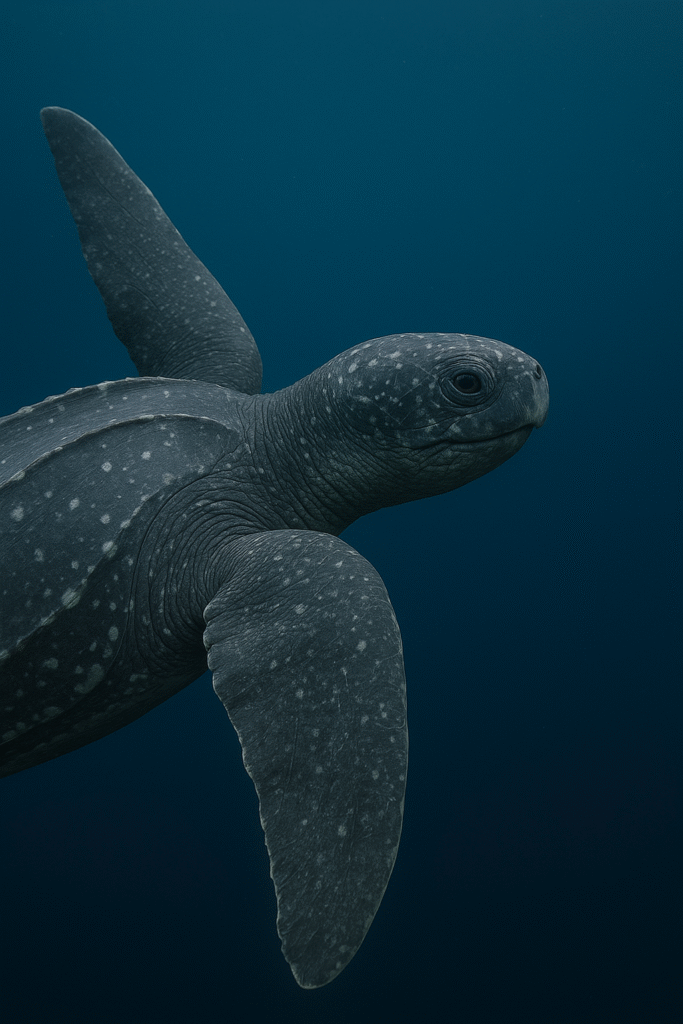

It is a paradox made flesh: at once ancient and futuristic, fragile yet indomitable, solitary yet woven into the fabric of oceans across the globe. Where other turtles carry bone armor, the leatherback carries memory. Its soft, rubbery shell ridged like the planks of a ship sets it apart from all others—a vessel designed for a different world, built to endure depths no reptile should have been able to reach.

A Creature of Depths

Most turtles hug coasts, reefs, or lagoons. The leatherback plunges into the abyssal twilight, routinely descending over 1,200 meters where sunlight dies and pressure could crush a submarine. Its body is adapted in ways scientists still puzzle over: collapsible lungs to withstand the squeeze, oxygen-rich blood to fuel dives, and a core that remains warm even in near-freezing waters. Unlike other reptiles, it is partly endothermic—an internal furnace in a cold-blooded frame.

Its prey is otherworldly: jellyfish, creatures older than trees, drifting like translucent lanterns in the dark. With jaws lined not by teeth but by backward-pointing spines, the leatherback swallows them in vast numbers. One adult can consume its own weight in jellyfish daily, quietly shaping marine ecosystems by keeping gelatinous blooms in check.

Ancient Mariners

Fossils trace the leatherback’s lineage back 110 million years—long before humans, long before whales, even before most flowering plants. In its migrations, it bridges worlds: nesting on tropical beaches, then ranging thousands of kilometers into sub-Arctic waters. Satellite tracking has revealed journeys of 10,000 miles or more, voyages so precise they seem navigated by an unseen compass.

How does the leatherback know where to go? Some scientists point to the Earth’s magnetic field, others to the chemical signatures of the sea, perhaps even celestial orientation. Yet none fully explain the near-miraculous accuracy with which females return to the very beaches where they hatched, decades later, to lay their own eggs. It is as if memory itself is inherited, written into the deep architecture of their DNA.

Stories of the Turtle

To encounter a leatherback is to encounter myth itself. In Caribbean folklore, it was the “Old Man of the Sea,” guiding fishermen through storms. In Pacific Islander cosmology, its ridged back resembled a celestial map, the turtle carrying stars upon its shell. To some Polynesian navigators, the turtle was a symbol of guidance and rebirth, its cycles mirroring those of the moon and tides.

In West Africa, coastal communities regarded the turtle as both food and ancestor, a creature bridging land and sea, the mortal and the divine. In modern conservation stories, it has become an icon of endurance and fragility—an ambassador for the oceans that asks us, wordlessly, to reconsider our place in the living order.

The Ritual of Return

Few sights in nature are as moving as a leatherback’s nesting ritual. Emerging from the surf under cover of night, the massive female hauls her bulk—sometimes exceeding 900 kilograms—onto the sand. With her rear flippers she digs a chamber deep into the earth, deposits up to a hundred leathery eggs, then covers them with sand before vanishing once more into the dark tide.

What follows is a silent gamble with time and fate. After about two months, the hatchlings break free, synchronizing their climb so that together they flood the surface like sparks from a hidden ember. Drawn by the shimmer of moonlight on water, they race toward the waves—unless artificial lights lead them astray, pulling them inland where survival is impossible. Only one in a thousand will live to adulthood. Yet the cycle continues, as it has for millions of years.

A Species Under Siege

The threats are modern and relentless. Plastic pollution is perhaps the greatest. A drifting bag resembles a jellyfish, and one mistake can be fatal. Entanglement in fishing gear, loss of nesting beaches to coastal development, and climate change (which skews hatchling sex ratios by warming the sand) all converge on this single species.

In the Pacific, some populations have collapsed by over 90% in the past four decades. Beaches that once thundered with nesting females now lie silent. The ancient odyssey of the leatherback risks breaking within a single human lifetime.

Guardians of the Tide

And yet, there is resistance. In Trinidad, villagers stand watch on nesting beaches, ensuring no poachers disturb the mothers. In Costa Rica, conservationists transplant vulnerable nests to hatcheries safe from flooding tides. In California, laws now restrict fishing practices that once ensnared turtles. Across the world, indigenous knowledge and modern science increasingly join forces, seeing the leatherback not merely as wildlife but as heritage.

Every hatchling that reaches the water carries with it the possibility of continuity. Each mother that returns to her natal shore writes another line in the story of survival.

The Leatherback and Us

Perhaps the leatherback resonates so deeply because it mirrors our own contradictions. It is a being of immense endurance, capable of crossing oceans, yet it can be undone by something as trivial as a plastic wrapper. It is prehistoric yet desperately modern, its fate entwined with our consumer choices and climate decisions.

In many cultures, turtles symbolize time itself—slow, patient, enduring. The leatherback, then, is more than an animal; it is a reminder of deep time, of lives measured not in years but in epochs. When we protect it, we do not only save a species—we preserve a link to Earth’s memory.

Epilogue: The Vanishing Giant

To watch a leatherback slip beneath the surf is to witness the vanishing of myth into reality, and reality into myth. It leaves no song, no cry, only the shadow of its passage. In its silence lies a lesson: survival is not always loud, not always aggressive. Sometimes it is simply the act of carrying memory across oceans, of enduring when everything else changes.

The leatherback has done this for more than 100 million years. Whether it will continue depends on us.

Reply