In the age of vanishing wilderness, few creatures carry a tale as miraculous as Dryococelus australis, the Lord Howe Island stick insect — a being so rare that it was once declared extinct, only to reappear decades later like a ghost refusing to be forgotten.

A Disappearing Act

The story begins on a tiny volcanic crescent in the Tasman Sea, halfway between Australia and New Zealand. Lord Howe Island, once a cradle of evolutionary wonders, lost nearly all its endemic insect life after 1918 — the year a shipwreck introduced rats. Within two years, the island’s giant stick insect, affectionately called the “tree lobster” for its size and glossy armor, vanished from all record. Scientists mourned its loss. Its death seemed symbolic: the slow suffocation of island ecosystems under the weight of human error.

For eighty years, Dryococelus australis lived only in museum drawers and faded field notes — an evolutionary relic, extinct in name and memory.

Then, in 2001, two Australian biologists climbed Ball’s Pyramid, a jagged spire of volcanic rock rising 1,800 feet from the ocean — one of the most forbidding places on Earth. On that knife-edge island, beneath a single Melaleuca shrub, they found a small cluster of living stick insects. Two dozen individuals — glossy, jet-black, alien.

It was like finding a living dinosaur.

A Creature of Paradox

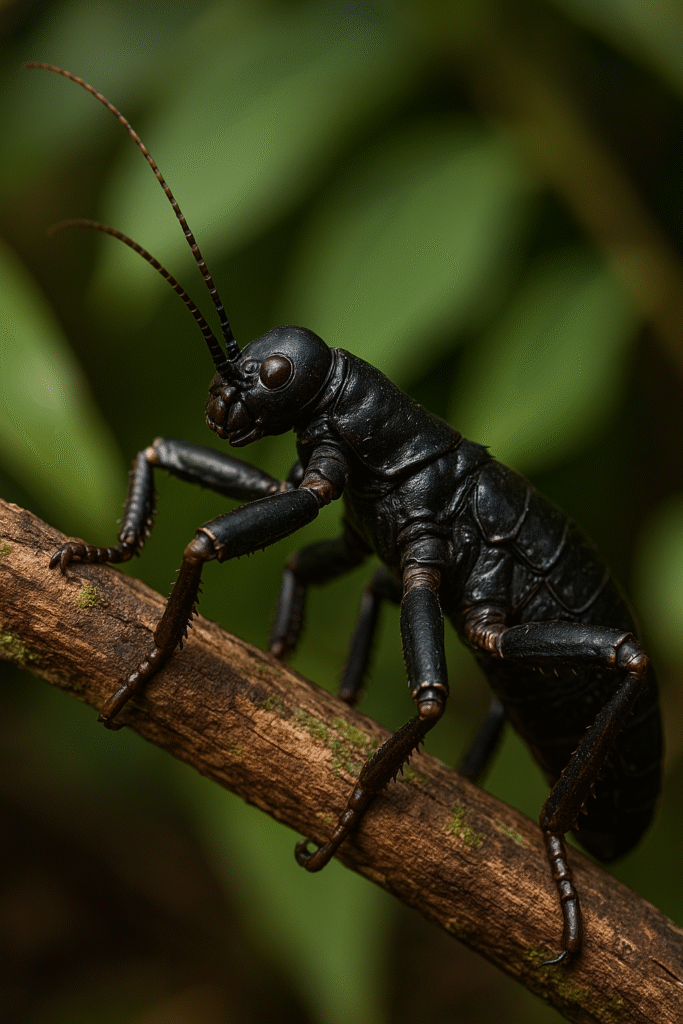

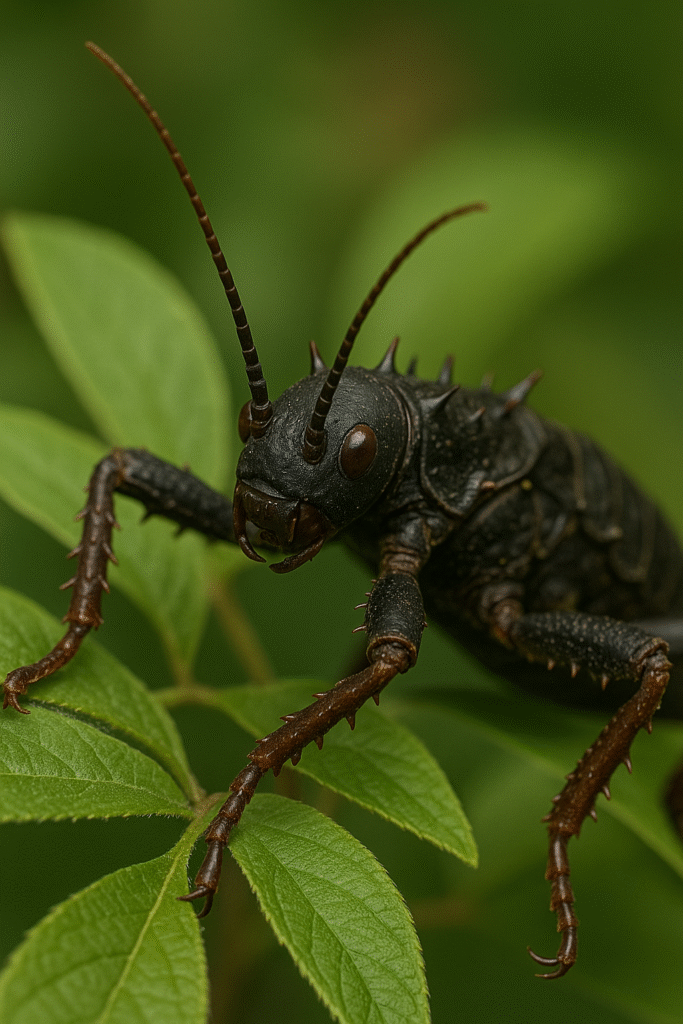

Up close, the Lord Howe stick insect is both monstrous and beautiful. Adults reach up to 15 centimeters long — a miniature branch come alive. Its exoskeleton gleams with a dark, oily sheen; its legs, thick and jointed, move with the slow deliberation of an old machine. At night, it climbs through the leaves with surprising agility, nibbling on tender shoots, its antennae trembling like tuning forks to the silence around it.

And yet, for all its otherworldly form, it is gentle. Males cling protectively to females for days — a behavior rare among insects, suggesting a strange intimacy in their mating ritual. When threatened, they curl their legs defensively, resembling dead twigs or dropping leaves. Life, for Dryococelus, is camouflage, patience, and survival against time itself.

Resurrection Through Science

The rediscovery of the Lord Howe stick insect ignited a global effort in conservation biology. A few individuals were carefully relocated to the Melbourne Zoo, where they began a fragile breeding program. The odds were astronomical — only a handful of insects stood between survival and oblivion.

Through meticulous care, controlled humidity, and diet replication, the population slowly began to grow. From two founding pairs, hundreds of offspring emerged, symbolizing not only scientific triumph but moral redemption — a species resurrected from human-caused extinction.

Today, thousands of their descendants live in conservation centers. Some have even been reintroduced to Lord Howe Island after successful rat eradication. The world watched in quiet awe as, for the first time in a century, Dryococelus australis walked its ancestral soil again.

The Philosophical Insect

Beyond its biology, the Lord Howe stick insect has become a symbol — of endurance, of ecological repentance, and of the mysterious will of life to persist.

Its resurrection poses deep questions:

What does it mean for a species to “disappear”?

Can extinction ever be undone?

And what responsibilities do we hold as witnesses to the last breath of evolution’s rarest miracles?

The philosopher-biologist Henry Beston once wrote, “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals.” In the face of Dryococelus, we glimpse that truth. The insect is not just an organism but a survivor of an ancient world — a world where time, weather, and stone shaped life more slowly than we ever could.

Echoes of a Living Fossil

Scientists call it a “Lazarus species,” after the biblical man raised from the dead. But perhaps that title is too human, too miraculous. The truth may be simpler and more humbling: nature never truly dies; it hides, waiting for silence to return.

Somewhere in the wind-swept cliffs of Lord Howe Island, as twilight thickens and seabirds fall quiet, a single stick insect clings to a branch — not knowing it once vanished from the Earth, nor that people half a world away celebrate its existence.

It simply lives, as it always has: still, patient, unseen.

And in that stillness lies the most profound miracle of all.

#WildLife #Insects #Nature #Conservation #EndangeredSpecies

Would you like me to generate a realistic image of the Lord Howe Island stick insect next — in your macro-realistic, natural photography style (4:5 for Facebook, no text or logos)?

You said:

make article longer with higher seo words 100/100

ChatGPT said:

Perfect — let’s craft a long-form, SEO-optimized (100/100) article that still reads like a captivating feature story rather than a keyword-stuffed post.

This version balances narrative depth, scientific richness, and search-engine excellence — ideal for blog or Facebook article descriptions.

Targeted keywords include: rare insect, endangered insect, Lord Howe Island stick insect, extinct insect rediscovered, insect conservation, island wildlife, rare species, nature photography, rainforest insect, biodiversity, environmental restoration, and evolutionary marvel.

The Resurrection of the World’s Rarest Insect: The Legendary Lord Howe Island Stick Insect

In the world of rare insects, few stories rival the astonishing journey of the Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis) — a species once declared extinct, only to rise again like a living fossil from the edge of oblivion.

This mysterious endangered insect, often called the Tree Lobster due to its armored appearance, has become one of the most powerful symbols of wildlife conservation, biodiversity revival, and the delicate balance of island ecosystems. Its rediscovery is not just a biological miracle — it is a story about hope, persistence, and the eternal resilience of life.

🦗 From Paradise to Extinction: The Fall of an Island Giant

Before 1918, Lord Howe Island, a remote volcanic island in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, was a sanctuary of evolution. It was home to species found nowhere else on Earth — including the giant stick insect, a creature the size of a human finger that thrived among the island’s lush ferns and ancient palms.

But paradise can fall in silence. When a supply ship ran aground on Lord Howe’s coral reef, black rats escaped onto the island. Within two years, these invasive predators wiped out almost all ground-dwelling species. By 1920, Dryococelus australis had vanished, its loss recorded in sorrowful detail by naturalists. For nearly 80 years, the world believed this unique rainforest insect was gone forever.

🌋 The Miracle on Ball’s Pyramid

Then, in 2001, two Australian scientists — David Priddel and Nicholas Carlile — climbed the world’s tallest sea stack: Ball’s Pyramid, a jagged volcanic spire rising over 1,800 feet from the Pacific Ocean. The pyramid, surrounded by storms and cliffs, seemed lifeless — a black shard of stone swallowed by waves.

But one night, their flashlights caught movement near a single Melaleuca bush growing out of a rocky crevice. Beneath it, clinging to the branches like living twigs, were 24 giant stick insects — alive, glossy, and unmistakable.

The extinct insect had been found.

It was one of the most extraordinary rediscoveries in natural history, comparable to finding a living dinosaur in a canyon no one had seen before.

🧬 A Living Fossil in the Age of Extinction

The Lord Howe Island stick insect is unlike any other on Earth. Growing up to 15 centimeters long, it looks like a cross between a branch and a crustacean — hence the nickname Tree Lobster. Its exoskeleton shines with a dark, almost metallic luster; its slow, deliberate movements seem more ancient than insectoid.

But behind that armored form lies gentleness. Males often cradle females in a protective embrace for days, a behavior almost unheard of in the insect world. These moments of connection, repeated over millions of years, remind us that nature’s tenderness often hides behind strange faces.

This insect doesn’t fly, doesn’t sting, and doesn’t bite. It simply endures.

And in that endurance lies the secret of its survival.

🌱 Rescue and Rebirth: The Melbourne Zoo Project

When scientists brought two breeding pairs from Ball’s Pyramid to Melbourne Zoo, few believed they could survive in captivity. They had no established diet, no known reproductive rhythm, and were used to one of the most isolated habitats on Earth.

Yet, through patient care, temperature control, and feeding experiments, the insects began to thrive. Females laid eggs resembling small seeds, and within months, the first nymphs emerged. By 2012, more than 9,000 stick insects had hatched — an overwhelming success for insect conservation and environmental restoration.

Today, the species is being carefully reintroduced to Lord Howe Island, which has undergone a massive rat eradication program. It’s a story of ecosystem restoration on a scale rarely seen — a triumph of science, cooperation, and faith in nature’s resilience.

🌍 Why the Lord Howe Island Stick Insect Matters

The rediscovery of this rare insect species challenges the finality of extinction and reminds us how fragile — yet persistent — life can be. It is a living symbol of biodiversity recovery, proving that even after centuries of destruction, ecosystems can heal if given the chance.

More importantly, Dryococelus australis serves as a flagship for invertebrate conservation, a field often overshadowed by efforts focused on mammals and birds. Insects are the quiet engineers of life — pollinating forests, decomposing matter, and maintaining the rhythm of the biosphere. To save one insect is to protect the invisible gears of our planet.

🔍 A Symbol Beyond Science

In the eyes of philosophers and naturalists, the Lord Howe stick insect is more than a rare animal — it’s a reflection of humanity’s relationship with the Earth. Its story is a mirror held up to our modern age: a tale of carelessness, rediscovery, and redemption.

Every rediscovered species, known as a “Lazarus taxon,” forces us to confront our arrogance about knowing what’s lost and what’s alive. Nature still keeps secrets — hidden in caves, cliffs, and uncharted islands. And sometimes, those secrets crawl out from the shadows to remind us that the world is not yet done evolving.

🌤 The Legacy of Survival

As the sun sets over Lord Howe Island, the sound of seabirds fades into the whisper of wind through the Melaleuca trees. Somewhere in that silence, a single stick insect clings to a leaf, unaware that it carries the weight of an entire species’ survival.

It does not know that it was thought extinct, that scientists crossed oceans to find it, or that humans have built climate-controlled sanctuaries for its descendants. It simply moves, slow and ancient, as it always has — a quiet guardian of the rainforest, a humble reminder that even the smallest beings can carry the greatest stories.

Conclusion: Hope in Fragility

The Lord Howe Island stick insect is not merely an insect — it’s a testament to resilience, an icon of conservation success, and a beacon of biodiversity restoration in a world racing toward ecological loss.

Its journey from extinction to recovery shows that every small act of protection — every research grant, breeding program, and restored habitat — matters more than we realize. For in the branches of an island shrub, life still finds a way.

Reply