Prologue: In the Ashes of Fire and Stone

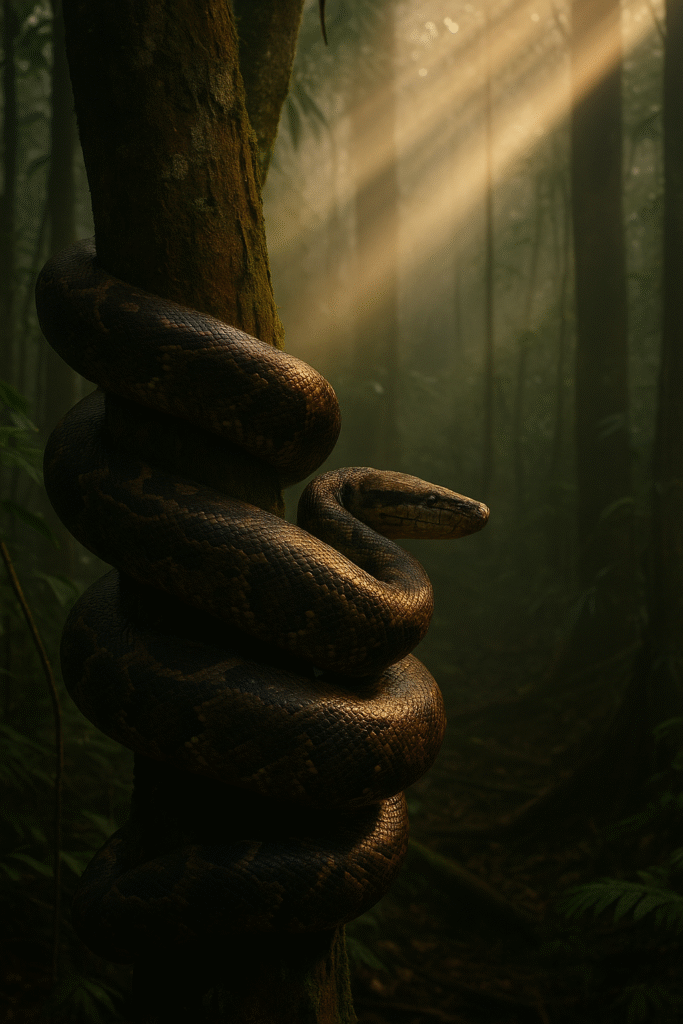

The volcanic island of Komodo burns with heat even when the sky is cool. Steam rises from fissures in the rock. The air carries the weight of sulfur and sea salt. Out of this landscape of flame and shadow emerges a shape that could belong to another world: low to the ground, scaled, and immense. Its tongue flickers like a black ribbon, tasting the air. Its claws sink into volcanic dust with each deliberate step. This is no creature of myth, yet it is the living echo of one: the Komodo dragon, survivor of deep time, standing as proof that humanity’s dreams of dragons were not born of imagination alone.

Here, in the creature’s amber eyes, glimmers the shadow of the dragon.

The Science of Reptilian Kings

Before they were myths, dragons were animals. Long before Homo sapiens carved their first stories into cave walls, reptiles reigned. Crocodiles, unchanged for over 200 million years, ruled rivers when dinosaurs were still young. Giant pythons, with their muscle-bound coils, hunted silently in the forests of Asia and Africa. Monitor lizards grew large enough to rival predators of legend.

The Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) is the largest living lizard — stretching over three meters, weighing more than 150 kilograms, its bite laced with venom, its claws honed for rending flesh. Crocodiles — Nile, saltwater, gharial — are among the most formidable predators alive, able to drown antelope, buffalo, and even sharks. Reticulated pythons and anacondas can swallow prey larger than themselves whole.

In these animals, biology and mythology intertwine. To meet a Komodo dragon, to hear the splash of a crocodile, to see the coil of a serpent is to understand why ancient cultures whispered: dragon.

Dragons in Myth

Every culture carved its own dragon into the world.

- In China, the lung was not a beast of destruction but a force of life — rivers, rains, and fertility. The dragon was emperor of water, benevolent and wise.

- In Europe, dragons were often monsters of greed and chaos — guardians of treasure, hoarders of flame. To slay a dragon was to become a hero, to conquer fear itself.

- In Mesoamerica, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl symbolized creation, renewal, and divine wisdom.

- In India and Southeast Asia, Nagas slithered between realms — protectors of sacred waters and guardians of cosmic balance.

- In Norse myth, the dragon Níðhöggr gnawed at the roots of the World Tree, a harbinger of decay and apocalypse.

Dragons are not merely monsters. They are metaphors: of chaos and order, wisdom and destruction, the unknown depths of earth and sky.

Encounters with Reality

Myth does not arise in emptiness. Ancient travelers saw crocodiles basking along the Nile and called them river dragons. Greek sailors glimpsed giant snakes in African jungles. Chinese fishermen knew of colossal pythons pulling birds from trees. On islands in Indonesia, rumors spread of enormous lizards with claws like daggers.

To eyes unaccustomed to reptiles of such scale, these were not animals — they were omens. Thus reality became myth. The Nile crocodile was worshipped as the god Sobek in ancient Egypt. Great snakes became messengers of gods. Even the bones of dinosaurs, unearthed by shepherds and peasants, became the fossilized remains of dragons slain by heroes.

The natural world gave us the dragon. Humanity gave it wings and flame.

The Archetype of the Dragon

Why does every culture dream the dragon?

The answer lies in psychology as much as zoology. Dragons embody what Carl Jung called an archetype — a figure born from the collective unconscious. They represent chaos, the primal danger our ancestors knew in the dark: the hiss of a snake, the splash of a crocodile, the rustle of a predator unseen.

Yet the dragon is also guardian, teacher, and threshold-keeper. To face the dragon is to face fear. To slay it is to grow. To befriend it is to gain wisdom.

The dragon is our shadow: feared, revered, but always present.

Crossroads of Culture

In the West, the dragon is to be conquered. St. George slays his beast. Siegfried pierces Fafnir. The dragon’s death becomes the birth of the hero.

In the East, the dragon is to be revered. Chinese emperors wore dragon robes, their thrones called “the dragon’s seat.” Dragons danced in festivals as bringers of luck, rain, and prosperity.

In Africa, great serpents are both ancestors and adversaries. In Indigenous America, the serpent is the rainbow bridge, connecting worlds.

The same animal — scaled, powerful, liminal — becomes either foe or guide depending on the lens of culture.

Modern Reptilian Monarchs

Today, the closest we come to seeing a dragon is in the presence of reptiles that echo their myths:

- Komodo dragons, patrolling volcanic islands with patience and venom.

- Saltwater crocodiles, the largest reptiles alive, lurking in estuaries with terrifying strength.

- Anacondas and reticulated pythons, capable of swallowing prey whole, legends given muscle.

- Gharials, with their long, strange snouts, like mythic beasts shaped by river gods.

These are not fantasies. They are real rulers of their realms, proof that the line between myth and reality is as thin as a flicker of scales.

Philosophical Reflection

To dream of dragons is to dream of power, chaos, wisdom, and fear woven together. To see a Komodo dragon basking in volcanic light is to feel myth made flesh.

Perhaps the dragon endures in us because it is the perfect mirror: it shows us the strength we desire, the fear we cannot escape, the wisdom we long for, and the chaos we must confront. The dragon lives both outside us and within us.

Closing Scene: Twilight on Komodo

The sun falls red across the island. The Komodo dragon moves along the ridge, its silhouette black against fire and sea. It pauses, tongue flickering, eyes fixed on the horizon as if watching something older than time itself.

In that moment, myth and reality are indistinguishable. The dragon has never left us. It still walks, in scales and shadow.

Reply