Rare moment: when a skull changed a century

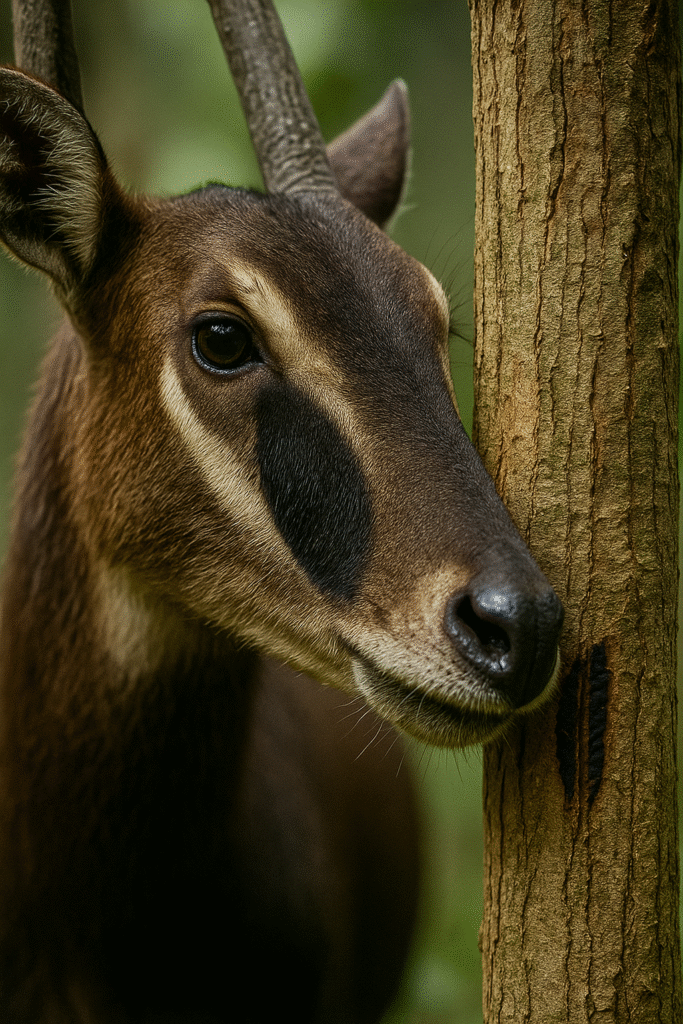

In the hot spring of 1992, biologists hiking a ridge between Laos and Vietnam found an antlerless skull in a hunter’s house: long straight horns, velvet-dark; a face marked with delicate white lines; glands flaring like small moons at the jaw. No book had this animal. Field teams fanned out, and the rumor grew bones. In a decade obsessed with satellites and speed, the forest had kept a large mammal secret. The world called it the Saola, the “spindle horn,” and for a brief, astonished season, it felt like the planet had handed us an extra chapter.

We have barely seen it since.

1) Identity: what the saola is (and isn’t)

- Family: Bovidae (cattle/antelope clan), but not a cow, not a goat; it is its own ancient branch.

- Look: Chocolate to sable-brown coat; long, parallel black horns on both sexes; fine white facial tracery; a strong maxillary scent gland like a polished, pale coin on each cheek.

- Size: Deer-like (80–100 kg), tall, refined, a quiet presence rather than a stamped hoof.

- Home: The Annamite Range—mist-stitched mountains along the Laos–Vietnam border; cloud forests, river gorges, wet leaf fall that smells of cinnamon and iron.

- Temperament: Crepuscular, shy, a specialist of shadowed paths; more forest antelope than open-country grazer.

- Rarity: Perhaps the rarest large land mammal alive. Most of what we know is inference stitched from tracks, camera traps, scent posts, and a handful of brief captures and releases.

The saola is not mythical. It is uncommon in the strictest sense: not many, not loud, not tolerant of broken places.

2) Majestic photography + storytelling: the ridge that breathes

Dawn on an Annamite saddle. Cloud spills below like milk deciding which valley to take. A dark, slender line resolves into horns; the animal steps without sound and the forest edits its outline with bamboo and fern. Dew lifts from its coat like breath. For three seconds the face turns—white pinstripes, calm eyes, the pale disk of a scent gland bright against green gloom—then the ridge inhales and the saola is written back into foliage. Photographs of wild saola are almost nonexistent; the story is what the place leaves you with: depth, damp, and the discipline of moving softly.

3) Survival battle: a unicorn versus a wire

The saola’s predator is not a tiger; it is cheap wire bent into a loop. Millions of snares pepper the Annamites—indiscriminate, quiet, unarguable. They wait for any leg, any neck. A saola that steps wrong doesn’t get a chase; it gets a countdown. Snares were set for pigs and muntjacs; they take unicorns because wire does not care for names.

Where forest law is thin and demand for bushmeat or wildlife parts is strong, snares multiply. They make extinction a process, not an event: slow bleed-offs of breeding adults, empty years without calves, an absence that becomes the new normal.

4) Emotional animal rescue: the snare team’s longest day

Rangers followed a dog’s point to a steep cut where bamboo met rock. The wire was old but the wound was new, a tight spiral that had already tattooed the skin. They hooded the saola—dark cloth, light hands—cut fast, flushed the wound with clean water, and eased antibiotic along a line of punctures. The head stayed still; the ribcage trembled. They held until the breath found rhythm, then walked the animal to a cool draw and waited. It stood, looked through them like rain looks through leaves, and stepped into the dark water of the understory. The team stayed silent for a long time, then followed the map of snares back down and pulled wire for hours.

Not every rescue ends with a glide into shade; many end in necropsy notes and anger. But each successful release is a proof that skill plus time plus will can bend a graph.

5) Strange/camouflage creature: scent coins and silent keys

The pale oval on a saola’s cheek is a maxillary gland, larger and more prominent than in most bovids. Pressed on sapling or stone, it writes scent sentences in a forest language—ownership, readiness, identity. The body is a design for quiet: small hooves to read slick rocks; slim limbs for steep switchbacks; coat oils that shrug rain. Horns stand parallel like a tuning fork; the face stripes repeat the run of light through bamboo, a camouflage of geometry rather than color.

6) What you didn’t know (and will tell someone)

- A new mammal—almost yesterday. Described by science in 1993; a once-in-a-century discovery of a large terrestrial mammal.

- Parallel horns on both sexes. Not antlers (no annual drop); true horns sheathed in keratin, near-perfectly straight.

- Scent-forward life. Oversized facial glands mark trails, crossings, salt licks; chemistry composes community.

- Water is a rule. Sightings cluster near cool, fast streams with intact canopy—a natural air-conditioner in humid heat.

- Low reproductive tempo. Likely single calves; slow replacement magnifies adult deaths.

- Silent diet. Browses tender shoots, leaves, and figs; not a grazer of grass but a picker of understory.

- Dog danger. Free-ranging hunting dogs push saola into panicked flight where snares wait.

- Forest needs to be whole. Edge-happy forests invite pigs and people; unicorns live in core.

- No zoo safety net. There is no viable captive population; the species must be saved in place.

- Communities hold the key. The range is lived-in; success rides on local guardians, not distant decrees.

7) Symbolism, culture, mythology

Villagers knew the animal long before journals did. Names vary by valley—saola, spindle-horn, forest goat—but the feeling is consistent: rarity that tastes like blessing. In a region where dragons curl in river fog and mountains wear crowns of cloud, the saola reads as humble magic—no roar, no display, just presence. It is the unicorn that never asked for applause. That makes it perfect for a new conservation story: pride without possession, guardianship without spectacle.

8) Field guide: how to look without harm

You will almost certainly not see a wild saola. That is the point: the forest is still working. If you work these mountains, honor the animal by making the place better for it.

- Listen for absence. A snare line feels like a wrong sentence: straight sticks, oddly bare soil, faint trails with no hoof sign.

- Read crossings. Narrow, shaded stream fords with smooth rock and overhanging bamboo are highways for everything that needs cool feet.

- Cameras with restraint. If you must deploy camera traps, site them for non-target safety and check them infrequently; human scent and paths can invite poachers.

- Dogs on leads. A single chase can kill in a snare country; the right photo is the one not taken.

9) What works (and what only looks good)

Works

- Snares out, always. Weekly sweeps by paid, local teams; snare bounties that reward removal, not discovery; metal recycling that pays cash for wire.

- Community forests with teeth. Legal rights to enforce no-hunt zones; ranger jobs that buy schoolbooks and rice; pride campaigns that make intact forest the village brand.

- Targeted corridors. Reconnect cool stream gulches and ridge saddles; block new roads that slice core habitat into snare-friendly edges.

- Smart patrol tech. Quiet, off-app maps; metal detectors tuned for wire; acoustic sensors for dog packs; camera traps aimed at people, not wildlife.

- Evidence-led protection. If camera data suggest presence, shrink the circle of knowledge and raise the patrol tempo—security first, press later.

Looks good, fails

- Token releases into snare fields. A photo today, a carcass tomorrow.

- Unpaid volunteer patrols. Burnout breeds silence; salaries keep forests honest.

- Signs without sanctions. Poachers read signs as maps to value.

- One-time sweeps. Snares return in nights; patrols must be continuous.

10) Climate realism: heat, flow, and fog

The saola’s map is written in cold air and moving water. As climate shifts, low streams run warm, fog lines climb, and valley bottoms develop fevers. The defense is practical: protect headwaters, keep canopy unbroken, and ban mining/logging that silt streams. A forest that holds water holds saola.

11) Personal narrative + moral: a lesson in humility

We worked a ridge all morning and found only stories: cut wire, a scuffed sapling, two ovals of scent just faint enough to doubt. In mid-afternoon a storm rinsed the heat, and the forest changed key. Somewhere in that cool music an animal with straight black horns crossed a wet stone without slipping. We didn’t see it. That felt right. Some successes you measure by what remains unseen because it still exists.

The moral is plain: Extinction by snare is a policy choice. Replace wire economics with forest economics—jobs, pride, enforcement—and the unicorn keeps walking. Leave the wire, and the forest forgets its own miracle.

Fast FAQ

Is the saola a kind of antelope?

Yes—family Bovidae—but it stands alone in its own genus, a very distinct lineage.

Why is it so hard to find?

Low density, quiet behavior, steep terrain, and decades of snaring have made it ultra-elusive.

Can we breed it in captivity?

There is no established captive population. Protecting wild animals and their corridors is the only realistic path.

What threatens it most?

Snares, plus roads that invite hunters and dogs. Habitat loss and climate shifts compound risk.

How can a reader help?

Support community patrol programs in the Annamites, back snare-removal funds, and choose products that don’t drive forest logging.

Closing

The saola is proof that the world still has new names for us—but only if we keep places where new names can live. The Annamites have written a unicorn into their rain; our job is to keep the page dry, the ink unfaded, the sentence unfinished.

Reply