Prologue: a real animal, not a rumor

In 1992, a team working along the Vietnam–Laos border found an unfamiliar pair of long, perfectly parallel horns hanging in a hunter’s home. They weren’t a deer’s tines or a wild cow’s crescent. They belonged to something science had never described. The discovery led to Pseudoryx nghetinhensis—the saola—an evolutionarily distinct forest bovid hidden for millennia in the wet, cloud-cooled evergreen slopes of the Annamite Mountains. More than three decades later, the saola remains one of the most elusive large mammals on Earth: rarely photographed, never maintained in captivity, and likely reduced to only dozens—perhaps a few low hundreds—across fragmented pockets of habitat. This is the story of a species on the knife-edge, and of the precise, realistic plan required to pull it back.

1) Identity: what the saola is (and isn’t)

The saola is a bovid—related to cattle, goats, and antelopes—but it is not a deer, not an antelope in the African sense, and not simply a “goat in a raincoat.” It is the sole member of its genus, Pseudoryx, and that matters: when a species carries an entire genus with it, extinction deletes a unique branch of the evolutionary tree.

Field profile

- Shoulder height: ~80–90 cm

- Mass: ~80–100 kg

- Sexes: Both males and females bear long, nearly parallel horns (typically 35–55 cm), round in cross-section, tapering almost symmetrically.

- Coat & markings: Deep chocolate-brown body; crisp, pale facial chevrons; white above the hooves. The head mask—clean white lines framing dark eyes—is the fastest field cue after the horns.

- Feet & gait: Compact, sure-footed on steep, wet slopes; trails are narrow and low, more like a muntjac’s than a sambar’s.

Why the horns matter

Parallel, evenly tapered horns on both sexes strongly suggest forest movement through dense understory where snag-resistant headgear is an advantage. You can often infer ecology from shape; the saola’s skull reads like a map of the Annamites.

2) The stage: a mountain chain built for secrecy

The Annamite Range runs like a green spine between Vietnam and Laos, catching monsoon moisture on steep ridges. In the saola’s bands of evergreen and montane forest, water is constant, temperatures are cooler than the lowlands, and fog is a regular character. Slopes are abrupt; ravines are narrow; leaf litter is thick; and tree roots lace the ground like rope. Travel is slow. Visibility is short. This is a place that punishes general surveys and rewards methods that can “sense” wildlife without seeing it.

Micro-habitat

- Elevation: typically mid-elevations (roughly 300–1,200 m in many sites), where the understory stays damp year-round.

- Edges: the species avoids broad, sun-baked edges; detection is likelier in shadowed ravines with perennial trickles.

- Trails: saola use fine game trails—exactly where wire snares are set for pigs or deer. That single overlap explains much of the species’ silent decline.

3) A sparse timeline: from description to the present

- Pre-1992: Known to local communities under various names; unknown to science.

- 1992: Scientific description from horn morphology; a new genus is recognized.

- 1990s–2000s: A few animals are captured alive by villagers; none survive long in captivity, and no managed ex-situ population is established.

- 2013: A single camera-trap photo in central Vietnam provides the last unambiguous visual record in the wild.

- Late 2010s–2020s: Protected-area upgrades, community snare-removal programs, and method shifts (from “camera everywhere” to eDNA first) redefine how teams search.

- Today: A converging strategy: clear snares, detect with eDNA, confirm rapidly with targeted cameras, and—only when detections repeat—consider humane capture to seed a carefully designed assurance population in-range.

This is not a failure narrative; it is a transition from improvised hope to disciplined, testable workflows.

4) Population and status: what we can responsibly say

No one has a census. The terrain and the animal’s behavior make that impossible with traditional means. Still, multiple independent lines of evidence point the same way:

- Rarity of detections: Years can pass without a single image, even in intact forests.

- Snare saturation: Tens of thousands of wire loops are removed annually from some parks, and those are only the ones found.

- Small range + fragmentation: The species occupies narrow ecological bands; any break (road, logging front, long snare line) can sever a valley from the rest.

The conservative global assessment remains Critically Endangered, with very small and declining numbers. Many experts treat “fewer than 100 total” as plausible. Whether the true number is 60 or 260 does not change the prescription: the species needs a search-and-secure response scaled to rarity.

5) Threat analysis without euphemism

The primary, immediate driver is wire. Not targeted trophy hunting; not live animal trade focused on saola; not large carnivores. Indiscriminate snaring for general bushmeat sweeps the forest like a metal net. Saola die as bycatch. A snare doesn’t go home at dusk; it keeps killing silently for months. That is why patrol economics—funding local teams to remove wire every day—save more saola lives than any other single action right now.

Secondary pressures

- Fragmentation: Narrow ridges and ravines quickly become islands when roads push in.

- Edge effects: Drier edges change understorey composition and push snaring lines deeper.

- Information lag: Because saola detections are so rare, political urgency can fade between proofs; continuity of funding is essential to prevent “project whiplash.”

6) Detecting a ghost: how modern teams actually find saola

The old approach—deploy hundreds of camera traps and hope—wastes money and time in terrain that will break most hardware before it yields a picture. The modern workflow sequences non-invasive genetics before optics:

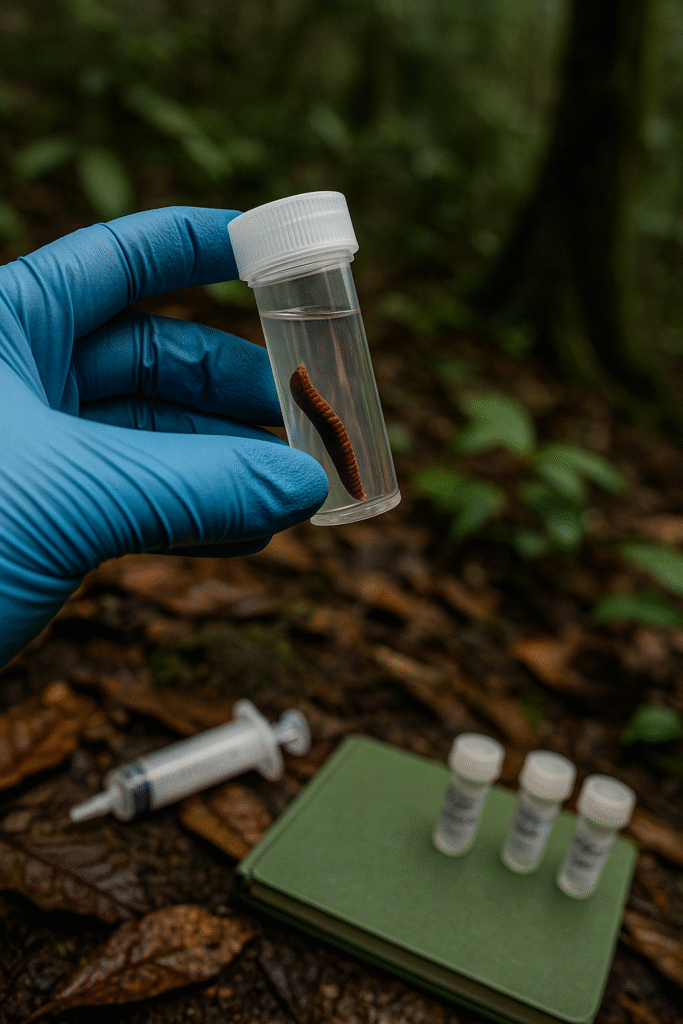

6.1 iDNA from leeches

Blood-feeding terrestrial leeches act like mobile syringes. They feed on mammals (and birds), then crawl away. Field teams collect them; labs extract ingested DNA (iDNA) and barcode it. One positive tube can tell you a valley holds saola without a single photo. Advantages: low impact, cost-efficient, and perfect for places where animals avoid cameras or where you cannot leave gear for months.

6.2 eDNA from streams

Every animal sheds cells—skin, hair, feces—into water as it crosses. Filtering upstream trickles captures that environmental DNA (eDNA). If a headwater drainage flags positive, the search grid gets small fast.

6.3 Short, dense camera arrays

Only after genetics point to a hotspot do teams deploy tight camera clusters for a short window (60–90 days). This reduces theft risk, maintenance load, and the temptation to “fish” with cameras across dead zones.

Why this works

In landscapes where walking 5 km takes half a day, the order of operations—sample → confirm → concentrate—saves months, reduces risk, and creates cleaner evidence for decisions like capture attempts.

7) The conservation playbook: step-by-step, no wishful thinking

Phase A — Hold the line (immediate)

- Permanent snare removal: pay trained local patrols; measure success in snares removed per kilometer and non-target mortality prevented. Patrols should be year-round, not “project bursts.”

- Seasonal eDNA baselines: sample the same drainages in wet and dry periods; keep lab turnaround to ≤ 2–3 weeks so field deployment follows evidence, not the calendar.

- Targeted cameras: deploy in valleys where eDNA/iDNA hits; withdraw promptly to preserve gear and reduce human trace.

Phase B — Founders, carefully (triggered by repeated detections)

- Humane capture protocols: only after multiple independent positives from genetics and cameras do you attempt a capture. Vets pre-stage; sedation kept minimal; any marginal animal is tagged and released, not held.

- Assurance population in-range: a quiet, forested facility (e.g., Bạch Mã National Park model) for quarantine, health screening, and pair formation. All design choices—enclosure layout, noise limits, browse plantings—assume a high-stress, never-captive species.

- Genetic management: pairings guided by current structure (e.g., potential north–south lineage differences); avoid unnecessary relatedness; bank germplasm early.

Phase C — Return & resilience (mid-term)

- Guarded release landscapes: establish long-term community guardianship; certify valleys as snare-free with third-party audits; control access to maintain quiet.

- Post-release monitoring: use dung eDNA and camera recaptures to track survival, reproduction, and dispersal for at least five years per site.

- Adaptive management: treat each release as an experiment with pre-declared success criteria; adjust protocols after every season based on data, not sentiment.

8) Designing the first viable assurance population (practical details)

Site & biosecurity

- Noise & visual shielding: enclosures sited in forested pockets with earth berms or bamboo screens; no public viewing.

- Veterinary isolation: quarantine pens and treatment rooms separated by airflow and footbaths; every entry tracked.

- Diet: start with wild browse from the local floristic list; supplement gradually; gut microbiome monitoring is non-negotiable.

Capture to crate

- Trigger threshold: at least two camera confirmations and two independent eDNA/iDNA hits from a single valley within a short temporal window.

- Capture team: lead vet, anesthesia tech, field trackers, community liaison; contingency plans for heat stress and aspiration.

- Transport: shaded, well-ventilated crate; shock absorbers; direct route under 6 hours if possible.

Pairing & welfare

- Visual contact, physical separation at first; monitor cortisol (fecal) and behavior; progress gradually.

- Enrichment mirrors natural foraging: scattered browse, hidden mineral licks, varied floor textures.

- Exit ramps: if an individual fails to adapt, release with telemetry into a cleared valley rather than force acclimation.

9) Metrics and money: how to prove progress

Conservation fails when it can’t show what good looks like. For saola, publish and revisit a short, hard list of indicators:

- Snare pressure: snares removed/km; repeat surveys showing downward trends over ≥3 years.

- Detection cadence: number of eDNA-positive valleys/season; time from eDNA hit to camera confirmation (target: shortening over time).

- Health & genetics: parasite loads, injury rates, and heterozygosity indices for any managed individuals.

- Demography: calf survival and female fecundity in any reinforcement area; time to first wild-born offspring post-release.

- Financials: cost per snare removed, per eDNA run, per confirmed detection; transparency keeps donors and ministries aligned.

10) Communities first: the human architecture of success

Wire doesn’t hang itself. People set snares because snares put protein and cash on the table. You don’t fix that with slogans; you fix it with predictable income and pride.

- Paid patrols with benefits: stable salaries, insurance, and recognition—so removing wire is a career, not a gig.

- Market-proofing: support protein alternatives that scale (fishponds, poultry, agroforestry) and don’t collapse when a donor leaves.

- Cultural capital: document and celebrate local names/stories of saola; fold elders into detection teams; when the species resurfaces, communities should be the protagonists, not spectators.

11) Why the saola matters far beyond one mountain range

- Evolutionary distinctiveness: losing a monotypic genus is a much bigger loss than losing one of many similar antelopes; evolutionary history disappears.

- Regional symbolism: the saola is a shared emblem of Vietnam and Laos; cross-border cooperation around a positive icon builds diplomatic muscle that can spill into broader forest governance.

- Proof of method: if eDNA-led, snare-first conservation can rescue a large, ultra-elusive mammal, the same blueprint scales to other “phantom” species: Annamite striped rabbit, Edwards’s pheasant, and more.

- Hope with accountability: the saola is rare enough to demand rigor but visible enough (horns, markings) to rally public attention when images finally come.

12) Media that helps, not harms

- Avoid sensational myths. “Asian unicorn” is a hook, but overuse turns a real animal into a mascot. Emphasize wire snares and evidence-led work, not fantasies.

- Show the tools. Photos of leech sampling, stream filtering, and snare piles teach audiences how conservation works.

- Get the map right. Publish generalized locations (district/park level), never exact valleys; the wrong map pin invites the wrong visitors.

13) Frequently asked (and answered)

“Can’t we just breed them in a zoo?”

There is no captive population. Past ad-hoc holding attempts failed. Any assurance population must begin with carefully sourced founders in a purpose-built, in-range facility designed around stress reduction, browse diets, and biosecurity.

“How many are left?”

No one can give a precise number. The correct stance is: very few, trending downward, and still findable with modern methods if we keep pressure on wire and sample the right valleys.

“Is the forest itself safe?”

Large blocks remain, but fragmentation and snare density make “paper parks” meaningless. The only parks that matter are the ones that finance and measure snare removal and publish results.

“Is it worth this effort for one species?”

Yes—because guarding the saola’s valleys protects a wide cast of co-occurring wildlife, restores forest function, and refines a method that can save other missing species. It is a keystone project masked as a single-species effort.

14) A realistic vision of success

Picture a field season that runs like a well-oiled lab: leech tubes labeled, GPS tracks logged, stream filters dried and shipped twice a week. A dashboard updates from the lab: two positives in the same drainage, three weeks apart. The team deploys cameras for 60 days. On day 41, a frame: white mask, parallel horns, a pause at the water’s edge. The team breathes—but they don’t announce. They confirm again. They clear more wire. A month later, two vets arrive at a field post with a crate and a plan that has been rehearsed a dozen times without an animal. Capture, check, decide: this one rides to quarantine; the next one, if weaker, goes back with a tag into a valley that has been emptied of snares and crowded with eyes that care.

A year later, there’s a different picture: a calf tucking under a mother’s flank on a rain-dark trail. Not mythology. Not a miracle. A result.

15) What readers can do that actually helps

- Back the people who remove wire—monthly, not once.

- Pay for lab runs—eDNA results drive smart fieldwork.

- Support the quiet facility—not a zoo vivarium, but a forest-ringed, biosecure space for founders.

- Share the method—teach others that modern conservation is evidence-led, not luck-led.

16) Closing: last light, not last rites

The Annamites often look like the inside of a cloud. In that drifting, wet light, a hoofprint fills with rain and disappears. For decades, the saola used that vanishing act as its only defense. It isn’t enough anymore. What will save the species now is not invisibility but infrastructure: salaries for patrols, steady lab pipelines, checklists for capture, and corridors that remain quiet. We do not need myths to rally behind; we need methods that work. If we keep our promises to the forest and to the people who live beside it, the saola will keep its promise too: it will still be there, stepping out of the cloud for the camera and then for us, long after the rumor has become a routine sighting.

Reply