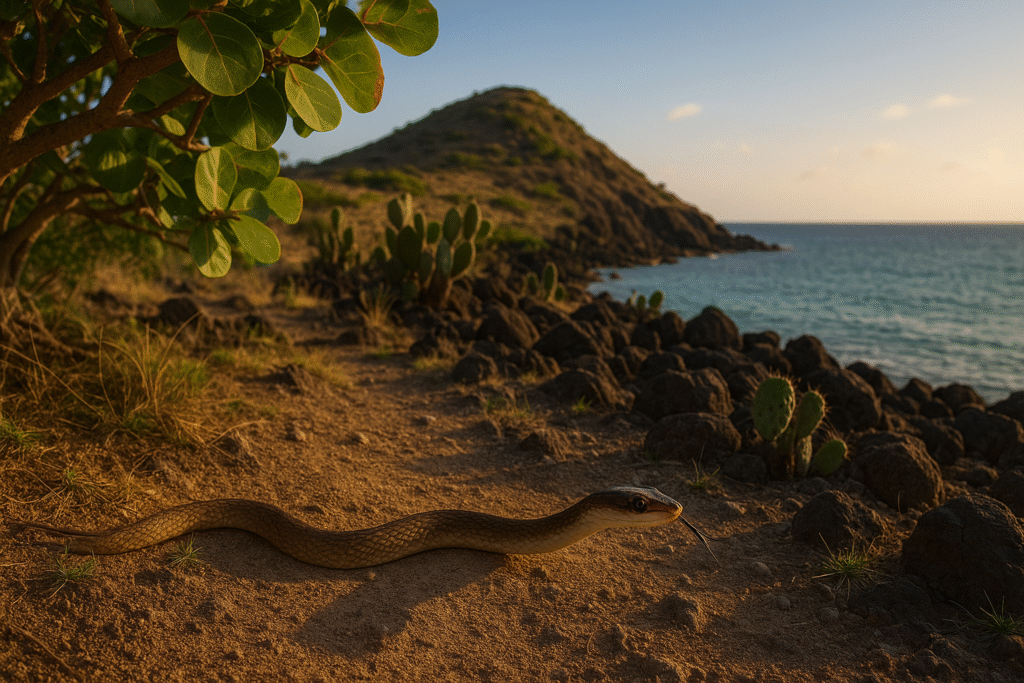

Rare moment: a ribbon in the windgrass

Saint Lucia racer snake is the focus of this story.The islet was all sunlight and salt: dry wind through goat grass, gulls stitching white arcs above black lava. We walked slowly, watching for the flicker that is not a lizard. At the edge of a sea grape, the ground drew a line and the line became a snake—brown like dusk, pale chin, eyes bright as seeds. It didn’t coil or threaten. It investigated the air, tongue writing brief questions. For a species once written off by science, this calm curiosity felt like a miracle you could count in breaths.

You are looking at the Saint Lucia racer, a harmless, diurnal hunter that may be the world’s rarest snake—a reptile that survived not by hiding in a rainforest but by retreating to a rock too small for its enemies to follow.

1) Identity: what the racer is (and isn’t)

- Taxonomy: Family Colubridae; Erythrolamprus ornatus (formerly Liophis).

- Look: Slender, 80–120 cm; olive-brown to chocolate dorsum with subtle flecking, a pale belly, and a refined head with expressive eyes. Juveniles can show crisper patterning.

- Temperament: Non-venomous, diurnal, and remarkably tolerant of gentle handling during research—more curious than combative.

- Diet: Lizard specialist—primarily anoles and whiptails—plus small frogs when seasons allow.

- Home today: Tiny offshore islets just off Saint Lucia’s coast—dry scrub, cactus, sea grape, and sun-cracked basalt with lizard-rich clearings.

- Home once: The main island of Saint Lucia, across multiple habitats, before invasive predators (notably mongoose and rats) erased it from most of its range.

The name “racer” fits the gait, not the temper: it can move like a drawn bowstring across open rock, but it spends much of the day as a measured naturalist—nose in leaf litter, charting the air.

2) The disappearance (and return) of a mainland snake

The island mongoose is a story that repeats across the Caribbean: an imported predator brought in to control rats in sugar cane, which then emptied native reptile populations instead. On Saint Lucia, the racer—ground-hunting and diurnal—was hit especially hard. By the late 20th century it was considered extinct. Then came the rediscovery on a small predator-free islet, a population clinging to hot rock like a final period at the end of a paragraph.

Why the islet worked: no mongooses, no feral cats, no pigs, and manageable rats after targeted eradication. Lizards were abundant, cover adequate, and human disturbance minimal. An ark, not a palace—but enough.

3) Anatomy of a gentle hunter

- Vision & tongue: Daylight-active with keen vision for motion; tongue-flicks map scent trails of skittery lizards under blazing sun.

- Strike & swallow: A quick pinning strike and immediate swallowing head-first; no constriction, no drama.

- Heat craft: Uses mosaic shade—sea grape and boulder shadows—to avoid overheating between pursuits; will flatten slightly to shed heat on windward rock.

- Shed cycles: In dry seasons, shedding proceeds slowly; racers often rub against sun-rough lava to start eye cap lifts. Researchers monitor shedding as a hydration proxy.

Everything about the racer is tuned to scarcity and glare: efficient search, brief sprints, long rests with eyes like polished pebbles.

4) Survival battle: a lizard economy on a knife-edge

On a rock this small, every calorie counts. A sunny hour brings lizard activity and opportunity; a cloud shelves the hunt. Female racers must time egg production to the lizard boom while avoiding the hottest weeks when moving is expensive. A single storm that floods burrows can reset a cohort. This is conservation measured not by forests saved but by days without a mishap—no rodent reinvasions, no illegal campers, no careless fire.

Predators are now mostly aerial: kestrels, herons, and frigates. The snake’s best defense is geometry—moving along boulder bases where raptors hesitate to stoop and freezing into shade when shadows pass.

5) Emotional rescue: the bucket with air-holes

Field teams occasionally find racers tangled in derelict seine line or wedged under a dislodged board. The protocol is quiet competence: shade the animal, cover the head with a soft cloth, cut fibers away with rounded-tip scissors, swab abrasions with sterile saline, and release at once if reflexes and righting responses look normal. When dehydration is suspected, a small drip line (never force water into the mouth) and an hour in a ventilated, cool “recovery bucket” can turn a failing snake into a swift ribbon again.

This is not heroics. It is first aid for a story too rare to lose to litter.

6) Strange/remarkable: island tameness

The Saint Lucia racer is among the least defensive snakes on Earth. In predator-free generations, many island reptiles lose the reflex to bite; the racer seems to have traded threat displays for investigative behavior. For researchers it is disarming—an endangered snake that looks you over as if you were another rock. For conservationists it is a warning: recolonize the island with a single mongoose and a population built on trust collapses overnight.

7) What you didn’t know (and won’t forget)

- Diurnal snake in the tropics. Most island snakes are crepuscular or nocturnal; the racer keeps banker’s hours.

- Egg-laying minimalist. Small clutches—think quality over quantity—make adult survival paramount.

- Shed as a health code. In hot-dry months, incomplete sheds signal stress; rangers track them to decide water caching.

- Non-venomous, non-constrictor. Purely a grab-and-swallow lizard specialist.

- Color honesty. No mimicry or bright warnings; the palette is the island itself—brown rock, pale sand, dried leaf.

- Population math. On micro-islands, a single storm surge or disease pulse can change numbers by double digits in one night.

- Silent services. By regulating lizard populations, racers indirectly influence plant pollination and insect cycles—many island lizards are pollinators.

- Genetic tightrope. Tiny populations risk inbreeding; careful translocations between safe islets can keep diversity afloat.

- Tourist risk. A dropped apple core can attract rodents stowed on boats; one pregnant rat is a disaster.

- Ambassador species. Its calm demeanor makes it an ideal flag for “snakes ≠ scary” education across the Caribbean.

8) Symbolism, culture, mythology

On Saint Lucia, old tales call snakes “ribbon spirits” of dry places—guardians of wells and watchers on hot paths. The racer fits: it keeps company with sun, reads the island’s breath at ankle height, and asks only for quiet rock. As an emblem, it is perfect for a new Caribbean narrative: island pride that chooses protection over fear.

9) Field guide for ethical visitors & creators

- Where (general): Small protected islets off Saint Lucia’s east and south coasts—permit-only; go with authorized rangers/guides.

- When: Morning into late afternoon; avoid peak noon on windless days.

- How to watch: Walk softly. Scan edges of shade under sea grape and prickly pear. If a snake stops to tongue-flick your boots, you are too close—take two steps back.

- Photography: 200–400 mm lenses; stay low, use natural light; no handling for photos.

- Zero traces: No food, no organic scraps; every crumb is a rodent risk. Sandals off boats get checked before stepping ashore.

10) What works (on islands where details decide)

Predator-proofing forever

- Keep mongooses and cats off-islets via strict biosecurity (rodent-proof bins, boat checks, landing protocols).

- Maintain rodent surveillance: chew cards, tracking tunnels, and rapid-response bait lines if signs appear.

Habitat like a lizard buffet

- Retain patches of sunny open ground for lizard thermoregulation.

- Conserve boulder labyrinths for snake cover; do not “tidy” rock piles.

Population nursing

- Mark–recapture to track survival and fecundity; microchips, not paint.

- If numbers allow, create a second and third insurance population on predator-free islets with similar lizard communities.

Community at the helm

- Pay and train local guardians; pair school programs with live-safe snake demos (racer temperament makes this easy).

- Tie visitor permits to conservation fees funding surveillance and habitat maintenance.

11) Climate and chance: planning beyond luck

Sea levels creep; storm tracks wobble. A micro-island plan must include storm refuges (elevated rock mounds, artificial crevice arrays), freshwater caches for drought months, and evacuation protocols if a once-in-a-century surge becomes a once-in-a-decade. Extinction here would not look like failure; it would look like complacency.

12) Personal narrative + moral: the lesson of a calm snake

We finished the transect and sat in a notch of basalt where spray sounded like torn paper. A racer appeared at our feet and considered us with the focus of a key inserted into a lock. It wrote a few questions on the air and slipped away, leaving the grass to remember it. In a world that often equates conservation with grand gestures, this snake suggests another path: small places guarded perfectly.

The moral is clear: the Saint Lucia racer is not asking for a new continent. It is asking for discipline—for boats checked, bins latched, rocks left, wire gone. Give it that, and a rare reptile remains ordinary on its rock, which is the highest honor we can pay any wild thing.

Fast FAQ

Is the Saint Lucia racer dangerous?

No. It is non-venomous and not aggressive. If you find one, admire from a few steps back.

Why is it called the world’s rarest snake?

Because it survives in tiny, isolated populations with very low total numbers. Rather than argue exact counts, the safe truth is: critically few.

Can it live back on the main island?

Only if mongooses, rats, and cats are controlled at landscape scale—an enormous but not impossible task in targeted zones.

Do we need captive breeding?

The priority is in-situ protection and multiple wild populations. Captive programs may serve as insurance, but they cannot replace guarded habitat.

How can readers help?

Support Caribbean invasive-predator control, fund islet biosecurity and monitoring, and share the racer’s story to defang fear of snakes.

Closing

Some species demand a wilderness the size of a country. The Saint Lucia racer asks for a few good rocks and the promise that nothing with a mongoose’s stride or a rat’s hunger will step ashore. Keep that promise, and a brown ribbon will keep running through windgrass under a Caribbean sun—a reminder that rarity can survive not by spectacle but by steadfast care.

Reply