Prologue: wind made into an animal

Stand on an open steppe long enough and the landscape begins to speak in the language of wind. Grasses lean and recover, dust creeps along the ground like water, and distances bloom and collapse with heat. Into this moving flatness comes a shape that seems drawn by the horizon itself: a sandy body on running legs and, where you expect a neat muzzle, a soft, downward-drooping nose—a living bellows that sifts dust, warms air, and turns the steppe’s violence into breath. This is the saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica), a survivor from ice-age grasslands that has learned to make weather part of its body. It is a creature of mass movement, sudden births, long hunger, and roads that are the wrong kind of straight.

The saiga is not just another antelope. It is a solution—an animal engineered by open country and seasons that change like doors slamming. To understand it is to read a manual for the steppe.

1) Identity: what the saiga is (and what it isn’t)

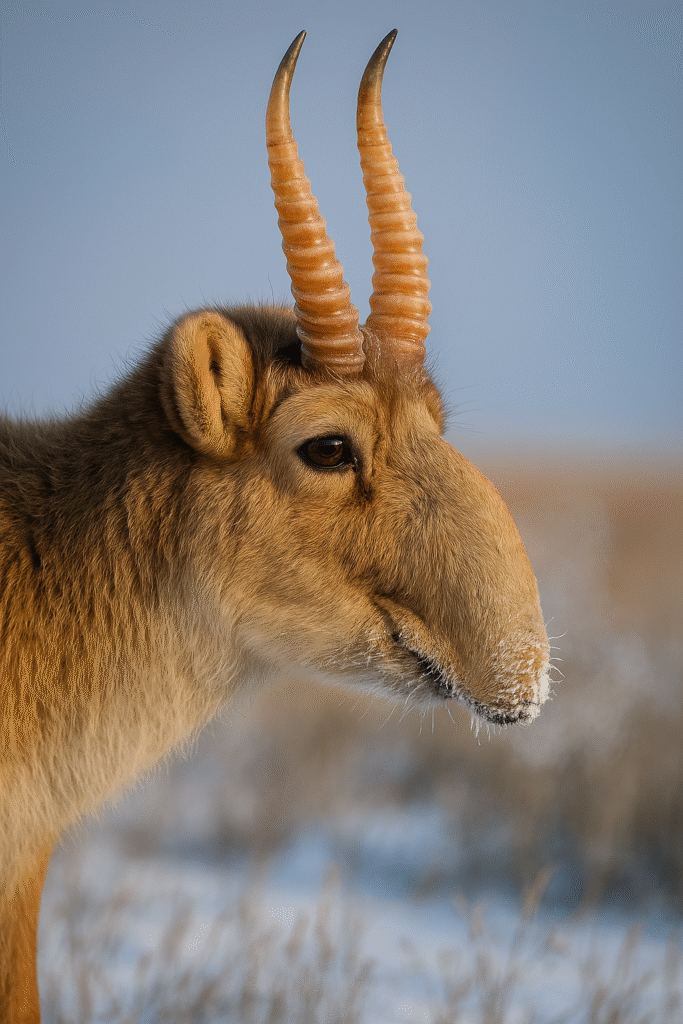

The saiga belongs to the family Bovidae, yet it overlooks the family’s tidy muzzles with its own proboscis—a flexible, inflated nasal structure that overhangs the mouth. Adults carry a pale, cinnamon-to-sand coat in summer that thickens and whitens in winter. Males grow amber, ringed horns that catch oblique sun like polished resin; females are hornless. Eyes are large and set wide; the gaze is always half elsewhere, as if measuring the next kilometer.

Key traits at a glance:

- Proboscis nose: filters dust, warms inhaled air in winter, cools exhaled air in summer—an integrated respirator.

- Cursorial build: long limbs, elastic tendons, and a body mass tuned for endurance over open ground.

- Sexual dimorphism: horned males heavier and more conspicuous; females smaller, built for distance and birth.

- Steppe palette: coloring follows the ground—blond, grey, and winter-white—so herds dissolve at distance.

Saiga once ranged widely across the Eurasian steppe; today they persist in continental grasslands and semi-desert where sky is most of the view.

2) The nose that makes a climate wearable

The saiga’s proboscis looks whimsical until you hold it up to weather. Dust storms on open ground are not a mishap; they are a season. Inhaled dust abrades lungs, saps strength, and invites infection. The saiga solves this with turbinate-rich nasal chambers wrapped in plush mucosa:

- Air filtration: the long nasal passages baffle and settle dust, trapping particles before they reach the lungs.

- Thermal conditioning: in winter, incoming air warms across a humid, vascular maze; in summer, water evaporates from the nasal lining, cooling the blood and shaving degrees off a hot body.

- Water economy: exhaled air passes back through the cooler mucosa; condensation recovers moisture that would otherwise be lost—crucial on saltpans and dry steppe.

Form is biography. The nose is a dictionary of wind, and the saiga reads it fluently.

3) A calendar written in hooves: migration and movement

Saiga are migratory ungulates built to redraw their own map. Movements are not leisurely—when green waves roll north with spring or south with early frost, the herds go as if pulled by string. Distances vary with snow, grass height, and water, but the logic is steady:

- Spring: move into newly flushed grass where protein is high and calcium is rising—perfect for late pregnancy and milk.

- Summer: track patchy rains, dodging heat by traveling at dawn, dusk, and night; seek open ground that keeps predators honest.

- Autumn: follow the last good forage south or to lower elevations; build fat against wind that will eat a body as surely as teeth.

- Winter: occupy sheltered flats or lee sides that collect less drifted snow, where digging to grass costs fewer calories.

Fences, pipelines, and roads are not obstacles in theory; they are obstacles in time. A migration blocked for a week is a herd thrown off its diet, its births, its chances.

4) Birth as weather: calving aggregations

The saiga’s birthing strategy is a bet placed on safety in numbers and timing. In late spring, pregnant females gather by the thousands into calving grounds on flat, open steppe where visibility is perfect and predators must approach under everybody’s gaze. Calving is synchronous—a burst compressed into days. Two results follow:

- Predator swamping: foxes, wolves, and eagles cannot take enough calves to dent the surge; losses are diluted in sheer abundance.

- Efficiency: the herd spends less time in vulnerable limbo and more time feeding hard, building milk, and moving out.

Twins are common; the steppe rewards a mother who can make two new racers from one winter’s fat. Calves lie low and scentless for their first days, pressed into grass like commas, then rise and run with the punctuation of a shout.

5) Social life: order formed by distance

Saiga herds are modular. Groups fuse and split like water. Outside the rut, females and young form trains that undulate across flats, while males drift at the edges or travel in separate bands. During the rut, horned males stake short-term territories and gather harems, their noses flushing and swelling with the season, their behavior a blend of display and brawling. The horns that make them beautiful also make them tired: fighting costs weight and sometimes life.

Communication travels as much in motion as in sound. Alarm is not a note but a ripple—heads rise, bodies tilt, the first line runs, and the whole shape follows.

6) Predators, parasites, and the quiet mathematics of risk

Wolves trail the steppe like moving stones; foxes mark the edges. Golden eagles and imperial eagles rake the newborn weeks. Yet the saiga’s most dangerous winters often carry no teeth at all. On open rangelands, risk is a stack of small, cold facts:

- Deep snow: grass hidden for too long is a starvation that moves on hooves.

- Ice crusts: freeze–thaw cycles knife pasture into glass; legs break, muzzles bleed, and calories burn for nothing.

- Parasites and pathogens: when bodies are thinned by weather or crowding, microbes take their chance; sudden die-offs are the boom-and-bust counterpart to a life that relies on abundance.

What looks like caprice—good years then bad—often maps to grass growth curves, snow physics, and the routes left open by the latest fence.

7) A Pleistocene memory walking on modern ground

The saiga’s bones lie in ice-age caves beside mammoth, bison, and cave lion. It is one of the few large herbivores from that era that still does the same job: turn temperate steppe into muscle and milk, then back into grass via dung and movement. It kept the job by being light, fast, and mobile—qualities that let a lineage sidestep glaciers and empires alike.

This deep pedigree explains the animal’s tolerance for cold and thirst and its need for space without negotiation. A saiga that must argue with a fence is a saiga living in the wrong century.

8) Diet and the art of selective speed

To a casual eye, the steppe is a near-monoculture of grass. To a saiga, it is a buffet of chemistries: short forbs rich in early protein, salt-tolerant plants that carry minerals where everything else carries fiber, and grasses at just the right stage—seedheads not yet tough, stems not yet straw. The mouth is small, the lips dexterous, the bite quick; the animal clips, moves, clips, moves—digestive chambers humming, microbes working at scale. Water is always in the calculus; saiga will travel to saline pans to balance their inner chemistry, then move back to sweetness as soon as rain resets the map.

9) Horns that cost more than bone

Male saiga horns are transparent amber, ribbed like topographic lines. They are beautiful enough to get males killed by people who want them as status, talisman, medicine, or trade. Horn demand turns the rut into a massacre: exhausted, conspicuous males are easier to approach; remove them and you leave females unserved, pregnancies interrupted, genetics constrained. The species’ biology—sudden abundance, visible male signals—collides with human preference in the worst way.

Enforcement helps; culture shifts help more. A horn left on a live male is worth a hundred rooms decorated with the past tense.

10) Roads, rails, and the thin line between “access” and “loss”

Steppe is famously empty until a straight line appears, then the emptiness becomes friction. A pipeline right-of-way, a railway berm, or a fence designed for stock, not wildlife, can act like a net. Saiga hesitate at narrow gaps, especially when young are small or snow baffles the senses; the delay pushes them onto poorer forage or deeper snow. Calving grounds abandoned for a single year may not be relearned easily—migrant memory is a chain made of mothers and calves repeating the same choices. Break it often enough and a map goes blank.

Wildlife overpasses, underpasses, and fencelines lifted high at regular intervals turn engineering into permission. The animal does the rest.

11) Mass mortality: when air, soil, and microbes conspire

Every few decades the steppe hands the saiga a bill for being many. Under certain combinations of humidity, temperature, and body condition, microbes that normally sit quietly in a saiga’s respiratory tract can bloom into hemorrhagic disease, rippling through a tight calving herd like flame. Carcasses appear overnight. The instinct to gather—so brilliant against wolves—betrays the herds against bacteria.

The answer is not to stop gathering; it is to protect movement so herds arrive at calving in better condition, spread across multiple grounds, and exit quickly. Resilience in a migrant is redundancy: more routes, more options, fewer single points of failure.

12) Conservation that works (and what only looks good)

Works:

- Anti-poaching grounded in community: hire locally, pay reliably, share data openly, and treat horn demand as a social problem, not only a policing one.

- Corridor protection: plan infrastructure with wildlife passage baked into design; retrofit critical legacy barriers with lifted wires, widened culverts, and snow-friendly underpasses.

- Calving ground quietude: seasonal closures for vehicles and herding; temporary, movable markers that shepherd traffic away without blocking wind or animals.

- Transboundary alignment: saiga don’t read passports; management must agree across borders on seasons, passages, and enforcement.

- Monitoring that predicts, not just records: satellites for snow and greenness; drones for herd position; disease risk models pegged to weather patterns and body condition so response is pre-positioned.

Looks good but fails:

- One-off roundups of orphaned calves—expensive, tiny in impact, and often unsuccessful.

- Symbolic “awareness” without demand reduction—slogans do not close markets.

- Paper corridors with no changes to fences or rails—maps don’t move animals; holes do.

13) A field guide for editors and readers

Name: Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica).

Look: sand-colored antelope with a downcurved, inflated nose; males with ribbed, amber horns.

Where: temperate steppe and semi-desert—the great Eurasian grasslands and plateaus.

Habits: migratory, forming vast herds; synchronous calving in late spring on open flats; strong seasonal coat.

Diet: short grasses, forbs, halophytes; selective grazer that tracks rain and salts.

Predators: wolves, foxes, eagles (calves); the worst years are weather and disease, not teeth.

Threats: poaching for horns, barriers to migration, extreme winters and ice crusts, disease pulses in dense calving herds.

Defenses: distance, numbers, proboscis engineering, and a map written in memory.

14) Science frontiers: questions that still matter

- Proboscis physiology in numbers: exactly how much dust is filtered, how many degrees of cooling are gained at given humidity, how water-recovery scales with pace.

- Migration learning: how calves encode routes—by following or by environmental cues—and how many missed years erase a path.

- Die-off forecasting: tying microbial bloom thresholds to weather, body condition, and plant chemistry; if we can predict, we can stage responses where they’re needed.

- Fence psychology: not just where to cut gaps, but what shapes and substrates keep nervous herds moving through in wind and snow.

- Calving ground fidelity: the strength of site attachment across generations; whether alternative grounds can be seeded by gently guiding early arrivers.

15) Management playbook you can start tomorrow

- Lift the bottom wire of livestock fences to wildlife-friendly height at regular intervals; mark and maintain them before migration, not after.

- Seasonal quiet zones around known calving flats; coordinate with herders and drivers months ahead; put people on the ground to help re-route.

- Rapid snow and green-up monitoring via open satellite data; share weekly maps with rangers and herders—information is migration’s best escort.

- Demand reduction targeting horn buyers with culturally fluent messaging and respected voices; pair with high-certainty enforcement to raise the cost of supply.

- Train mixed teams—rangers, herders, rail engineers—to walk lines together and fix small barriers before they become herd-level injuries.

16) Why the saiga matters beyond the steppe

The saiga is an argument, legible at a glance, that design can be a landscape. Its nose tells you what air does here; its migrations tell you what rain does; its births tell you where wolves find it hard to hunt; its deaths tell you how disease finds a crowd. Save the saiga and you keep grasslands whole—soils intact, carbon stored, winds tempered by living cover. You also keep an ancient co-evolution running: steppe plants clipped and fertilized in the same pattern that shaped them when mammoths still walked.

In a century of forests and reefs in crisis, the open country often goes underreported. A flat can be as rich as a canopy, and a kilometer of nothing can hold the rules for everything that can live there. The saiga is those rules, in bone and breath.

17) Closing: horizon animal

At dusk the steppe changes key. Heat loosens, sound travels, the smell of dust becomes the smell of plants again. A line appears where there was no line—dozens, then hundreds of saiga shifting from shimmer to bodies, from rumor to herd. The first calves hop like sparks, quick and illogical; mothers move like sentences that know where they end. A wind pushes, the herd leans, and for a few minutes you can watch weather and muscle agree on a direction.

What the saiga asks of us is not pity, nor even admiration. It asks for room, and for the right kind of silence—the kind made by lifted wires, unpatrolled calving grounds, and markets that decide not to turn amber into status. Give it those, and the horizon will keep moving, and the air will keep being turned into an animal that can wear it.

Reply