There are moments in natural history that resist the schedules of science. They cannot be predicted by migration charts, nor catalogued in field guides with any certainty. They happen in the in-between — the fog that rolls over marshes at dawn, the midnight surf breaking on a remote beach, or the silence just before a storm. These are the moments of rare encounter, when the natural world parts its curtain for just long enough to show us something so extraordinary, so improbable, that the memory lingers for a lifetime.

The Allure of the Unexpected

Humans have always lived in pursuit of these fleeting glimpses. Hunters of prehistory spoke of shadow-stags seen only once in a generation; fishermen told of whales larger than ships rising from deep waters and vanishing just as quickly. Even in our age of satellite tracking and thermal imaging, the element of surprise remains central to our relationship with the wild.

Rare encounters are not merely about rarity. They are about timing, place, and an openness to be astonished. A tiger walking through a misty tea plantation in Assam. A narwhal surfacing beside a kayak in the Canadian Arctic. A snow leopard revealed by a shaft of sunlight against barren cliffs in Ladakh. The rarity is not just the animal itself, but the fragile window in which human and nonhuman paths cross.

Science and Serendipity

From a scientific perspective, rare encounters serve as data points: the unexpected sighting that fills in a missing link in migratory maps, or the chance documentation of a species thought extinct. In 1938, a fisherman off South Africa caught a strange, armored fish. The creature, later identified as a coelacanth, belonged to a lineage thought to have vanished 65 million years earlier. A myth had swum into reality, and a rare encounter rewrote biology textbooks overnight.

Yet science cannot fully capture the feeling of such meetings. Field biologists describe their journals with words more poetic than empirical: “The gorilla looked at me and I felt the weight of centuries.” “The owl flew past, and it was like being brushed by history.” Behind the charts and measurements, there remains awe — the same awe that drove shamans, sailors, and storytellers of antiquity.

Myth, Symbol, and the Rare Animal

Civilizations built mythologies around rare encounters. When the ancient Greeks spoke of the phoenix, they were likely inspired by rare migrations of brilliantly colored birds like the flamingo or heron, appearing in the desert as if conjured from ash. The medieval unicorn was probably no more than a fleeting glimpse of a narwhal tusk or an oryx silhouette at sunset. But the myth endured because rarity itself demands explanation.

To witness what few others have seen grants power: the power of story, the power of connection to something larger than oneself. The rare animal becomes an emissary of the unknown, carrying with it a weight of prophecy, mystery, or warning.

Conservation’s Fragile Sightings

Today, many rare encounters are tinged with sadness. The saola, known as the “Asian unicorn,” has been seen by only a handful of people in the forests of Laos and Vietnam. The vaquita, a small porpoise of the northern Gulf of California, numbers fewer than 20 individuals; to see one surface is to witness both miracle and impending absence.

Photographs of such creatures circulate like relics — grainy images of ivory-billed woodpeckers, shaky videos of thylacine shadows in Tasmania. Each sighting ignites hope, yet also dread: hope that life endures where we thought it lost, dread that our gaze may be the last to fall upon it.

Rare encounters, in this sense, are time-sensitive miracles. They remind us that the line between existence and extinction is thinner than we want to admit.

Philosophy of the Rare

There is a philosophical undertone to rare encounters. They challenge our sense of control. In a world where data is harvested, species tagged with GPS, and ecosystems mapped, the rare encounter whispers: You do not know everything. The wild still has secrets.

This is not just humbling but necessary. Rare encounters reconnect us to the wildness of existence, to a recognition that not everything bends to human will or human comprehension. They teach us patience, attentiveness, and humility.

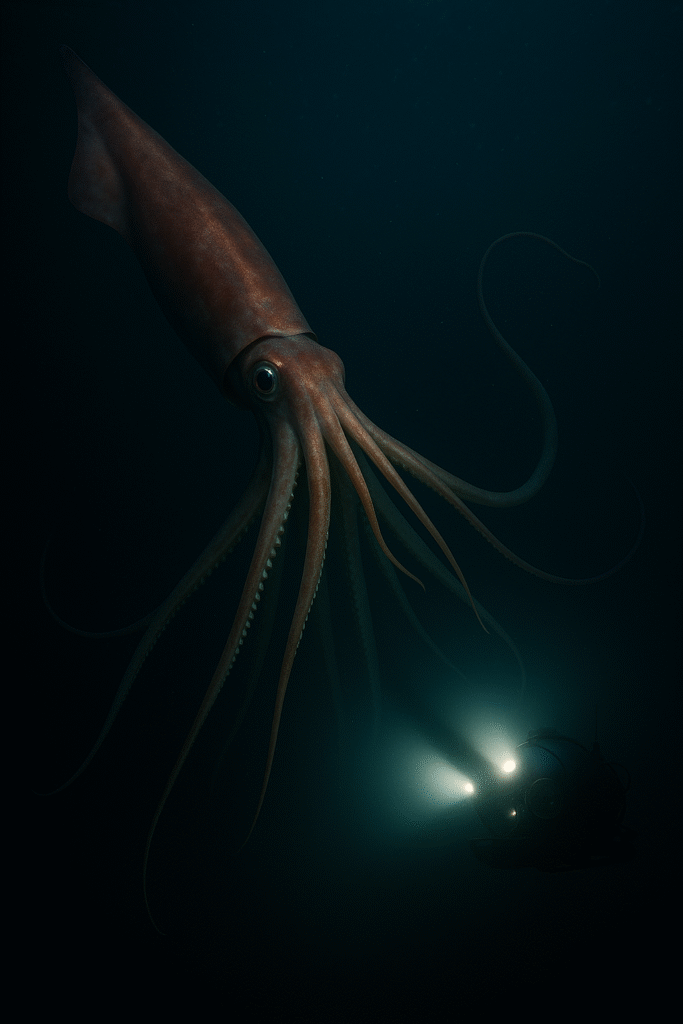

The theologian Rudolf Otto once spoke of the numinous — an experience of awe that is both fascinating and terrifying. To see a giant manta ray unfold its wings beneath your feet while diving is precisely this: beauty mixed with fear, grace intertwined with strangeness. It is the numinous alive in the natural world.

The Future of Encounter

The irony of our age is that technology both expands and contracts the possibility of rare encounters. Trail cameras, drones, and acoustic monitors bring us images of snow leopards in real time, yet they also make such sightings less “rare.” On the other hand, habitat destruction and climate change reduce the actual likelihood of stumbling upon these creatures in the wild.

Perhaps the rarest encounter today is not with a species but with silence — a rainforest without chainsaws, a reef without engines, a desert night sky untouched by electric glow. In these silences, even common creatures — an owl, a fox, a beetle — regain the aura of rarity, because we meet them on their own terms, in a world not yet saturated by noise and presence.

Closing Reflection

A rare encounter is not simply an event. It is an initiation — into humility, into wonder, into responsibility. The animal may vanish, the moment may pass, but something lingers: a sharpened awareness, a renewed reverence, a story carried forward.

When we meet the rare, we glimpse not only the fragility of nature but also the fragility of ourselves. For in the end, rarity is not just about numbers. It is about attention, about the courage to notice, and about the willingness to be changed by what we see.

Reply