Rare moment — hatchling under a thunder river

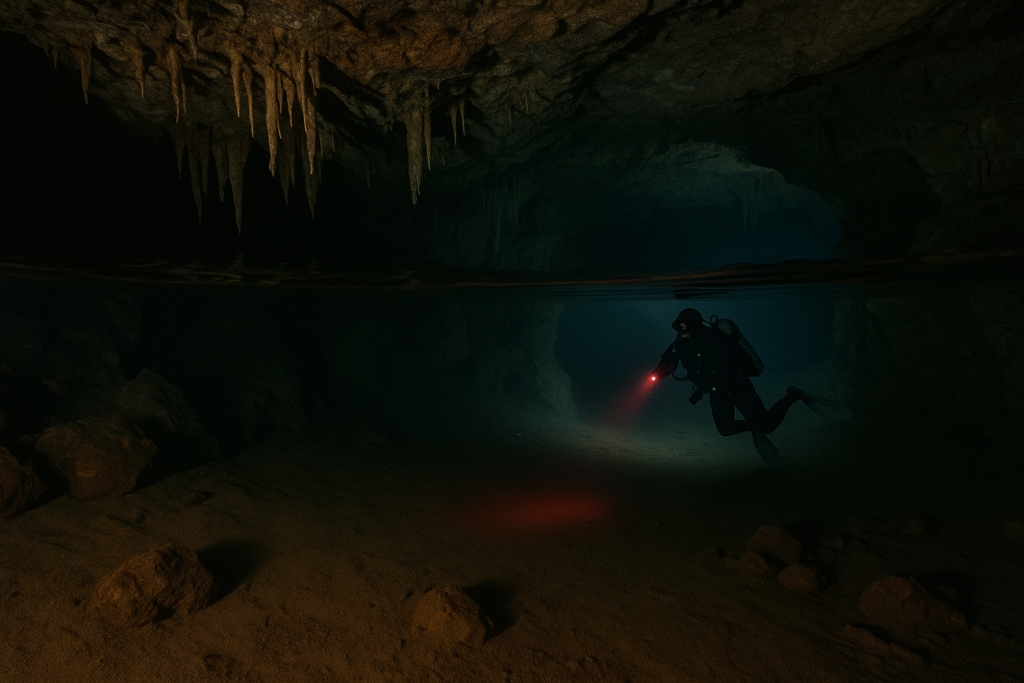

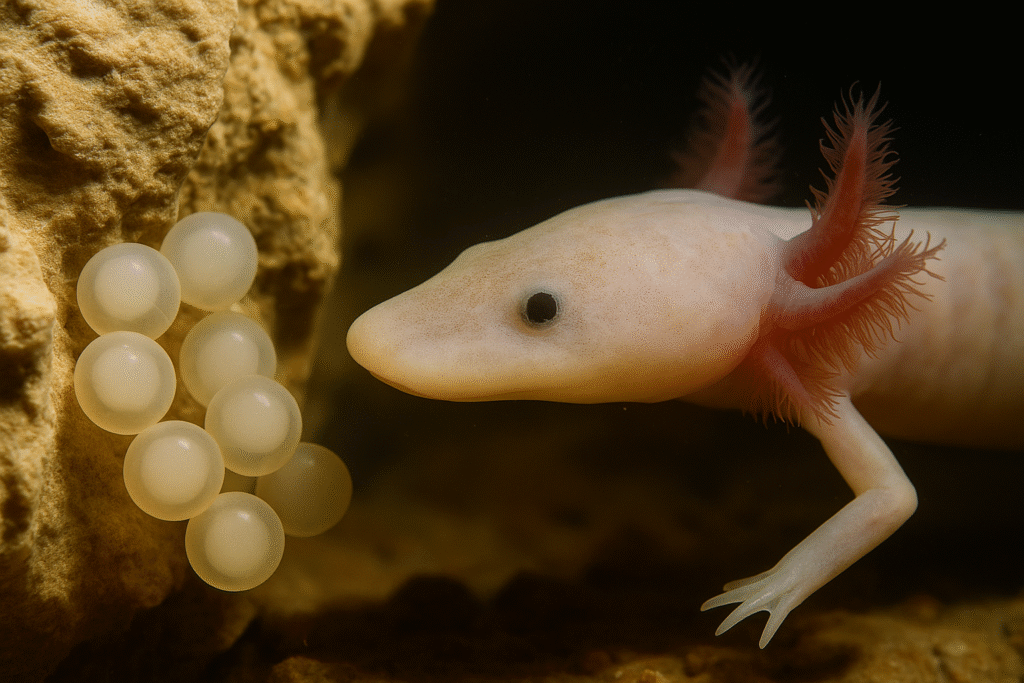

Olm cave dragon is the focus of this story. Balkan karst cave hummed with floodwater. Lights off, the gallery became sound and cold breath. Then a diver’s torch found it: a translucent larva clinging to limestone like a comma of living external gills flaming pinklaming pink, eyes sealed under skin. In a place where the sun has no jurisdiction, a new olm had joined a population that might not see another hatchling for years. It was a “rare moment” in a world measured by slow clocks.

external gills flaming pinkexternal gills flaming pinkOlm cave dragon is the focus of this story. A Balkan karst cave hummed with floodwater. Lights off, the gallery became sound and cold breath. Then a diver’s torch found it: a translucent larva clinging to limestone like a comma of living milk—external gills flaming pink, eyes sealed under skin. In a place where the sun has no jurisdiction, a new olm had joined a population that might not see another hatchling for years. It was a “rare moment” in a world measured by slow clocks.Olm cave dragon is the focus of this story. A Balkan karst cave hummed with floodwater. Lights off, the gallery became sound and cold breath. Then a diver’s torch found it: a translucent larva clinging to limestone like a comma of living milk—external gills flaming pink, eyes sealed under skin. In a place where the sun has no jurisdiction, a new olm had joined a population that might not see another hatchling for years. It was a “rare moment” in a world measured by slow clocks.

Identity: what the olm is (and isn’t)

- Class: Amphibia (order Caudata).

- Look: Pale to rose-white, eel-long body (20–30 cm), three feathery gills behind a blunt head, tiny limbs, eyeless (eyes reduced and skin-covered).

- Lifestyle: Fully aquatic, neotenic (retains larval traits for life), lives in total darkness of limestone caves in the Dinaric Alps (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Italy).

- Diet: Crustaceans, snails, insect larvae—caught by smell, touch, and electrical cues.

- Longevity: Among the longest-lived amphibians—many decades; growth and reproduction are glacially slow.

It’s not a fish, not an eel, and not a baby: it’s an adult that stopped “growing up” on purpose, because the cave rewards efficiency over change.

Olm cave dragon salamander – the focus of this story.

Strange/camouflage creature: a body edited by darkness

- No eyes, better everything else. Olms amplify chemosensation, lateral-line-like vibration detection, and even electroreception to read the water for prey and mates.

- Skin that listens. Without sunlight, pigment is mostly gone; the skin is thin and richly innervated, sensitive to pressure and ions.

- Red gills, pale blood. External gills flutter, trading oxygen in slow water; the heart loafs at cave pace.

- Fasting master. With a slow metabolism and big liver stores, an olm can fast for over a year, then rebound when food returns—survival by patience.

In a world of zero daylight, the olm’s color is karst itself: limestone turned to life.

Majestic photography + storytelling: the cathedral of drip

If you’ve never watched life by headlamp, an olm is a revelation. In a still pool under stalactites, the animal moves without wake, turning corners like thought. Every gesture is slow: a deliberate step, a feathered gill pulse, a pause that lasts long enough for your breathing to sound rude. Photographing one is like shooting silence.

Photo tips (ethical)

- No flash bursts; use constant low light with red filters.

- Shoot side-on to catch gill filigree and sensory pores.

- Backscatter is the enemy—hover, don’t fin; let silt fall.

- Never touch substrate near eggs or larvae; a single puff can smother them.

Survival battle: flood vs. famine

Caves swing between famine and flood. Famine teaches fasting; flood brings sudden food—and danger. Eggs and larvae can be dislodged; adults may be flushed into surface streams where sun, predators, and heat wait. Success is geology plus behavior: spawning in quiet back-eddies, retreating to siphons when rivers roar, and switching to ambush mode when the buffet arrives.

Emotional rescue: the bucket of darkness

After a spring flood, a speleology team found an olm stranded in daylight under a bridge, skin already pinking from UV. Rescue was not drama: a dark, cool, aerated bucket, water matched to cave temperature, quiet transport back to a known sump, release by hand up-current. The salamander slid into shadow and vanished between stones. The team logged coordinates and returned at night with signage: no wading in that reach after storms. The lesson wasn’t the save; it was the prevention.

Symbolism, culture, mythology

For centuries, villagers called them “baby dragons.” After heavy rains, pale bodies appeared in springs—proof that dragons bred in the mountain. Monks preserved specimens in jars; nobles kept them as curiosities. Today, the dragon myth is an asset: guides use it to teach that groundwater is a living system—pollute a sinkhole here, and a dragon dies in a cave downstream.

What you didn’t know about olms

- They hear with their skin. Specialized receptors make pressure and low-frequency sound actionable.

- They smell time. Olms can track chemical plumes so faint they function like slow news about upstream events.

- Two color forms. The famous white olm and a black olm (pigmented, surface-like eyes reduced) occupy different cave networks.

- Long childhood. Sexual maturity can take a decade or more; reproduction is irregular, tied to hydrology.

- Individual addresses. Adults often keep small home ranges centered on rock crevices—cave neighborhoods.

- Egg guarding. Females may tend eggs for weeks, fanning water and cleaning silt—a rare amphibian parental care.

- City water sentinel. Olm health mirrors drinking-water quality for millions in karst regions.

- No hibernation. Temperature is stable; instead of seasons, olms follow flow regimes and nutrient pulses.

- Low cancer incidence. Cave animals’ slow metabolism is a frontier for comparative biology.

- They can regenerate. Like many salamanders, olms regrow small injuries; slow living favors repair.

Field guide: where (generally) and how to look—without harm

- Where: Protected karst springs and show-cave systems in Slovenia and neighboring countries (some maintain off-display conservation labs).

- How: Go with licensed cave guides; many sites prohibit public entry to breeding galleries.

- Signs of presence: Cool, crystal pools; tiny crustaceans; bat guano threads; delicate silt fans.

- Do not: Shine bright lights, kick silt, handle animals, or enter restricted side passages.

Conservation: protecting a creature made of water

Threats

- Groundwater pollution: fertilizers, pesticides, septic leaks, industrial spills—caves are plumbing with no filter.

- Hydrological engineering: dams, gravel mining, and diverted springs alter flow pulses essential for breeding.

- Tourism pressure: light, heat, and silt from unguided visitation.

- Climate change: longer droughts punctuated by violent floods—bad for eggs and larvae.

What works

- Karst catchment protection—treat the entire recharge area as habitat.

- Nutrient and toxin buffers—regulated agriculture, sealed septic, emergency spill protocols.

- Egg-bank labs—ex-situ head-starting from locally sourced eggs, then return to native caves.

- Flood-smart infrastructure—keep heavy recreation out of spawning reaches during high-flow seasons.

- Citizen science for water—spring sampling networks that detect pollution early (eDNA + chemistry).

Personal narrative + moral

An olm glides like the memory of a river. Watching one, you realize how young most of our urgencies are. This animal’s answers to hard questions—eat less, move slowly, fix what breaks, wait—were written long before our schedules. The moral is simple: if we keep groundwater clean and flow honest, a small, breathing piece of prehistory continues writing itself in ink the color of limestone.

Fast FAQ

Is the olm blind?

Functionally, yes; eyes are reduced under skin. It navigates by smell, touch, vibration, and electric cues.

Can I see one in the wild?

Rarely and only with permits. Many countries offer ethical viewing of conservation-bred olms in darkened aquaria designed for zero stress.

How long can they live?

Many decades; some individuals may exceed a century.

Do they really go years without food?

They can fast for very long periods, slowing metabolism and recycling internal stores.

How can I help?

Support karst watershed protection, proper septic systems, and cave groups that monitor spring water quality.

Closing

The olm is Europe’s quietest flagship: a letter from antiquity still moving through stone. Protect the water, and the letter keeps traveling—pink-gilled and patient—through a chain of caves that connect farms, villages, and cities whether we notice or not.

Reply