In every age, humanity has sought ways to preserve its presence. We have spoken, sung, painted, carved, burned, and rebuilt, hoping that something of us might endure when we are gone. Yet of all the mediums chosen—clay, papyrus, parchment, wood, even light—stone remains the most enduring. Stone has no breath, no warmth, and yet it speaks. It remembers. It holds the weight of memory more faithfully than any scribe.

When we speak of antiquity, we do not mean simply “what is old.” We mean that which persists, that which continues to shape our imagination long after its makers have turned to dust. The legacy of antiquity is written in ruins, inscriptions, monuments, and artifacts—each a dialogue between the living and the long dead.

Mesopotamia: The Clay that Became Voice

Long before the age of marble columns and pyramids, Mesopotamian scribes pressed reeds into wet clay, inventing the world’s first written language: cuneiform. Kings such as Ashurbanipal of Assyria (7th century BCE) assembled entire libraries of these tablets, documenting everything from epic poetry to medicinal recipes. His great library at Nineveh, discovered in the 19th century, contained over 30,000 tablets.

Unlike papyrus or parchment, which decay quickly, these tablets hardened in fire—sometimes intentionally, sometimes during the burning of cities—and became time capsules. Because of this accident of endurance, we can still read the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known story, thousands of years after it was first inscribed.

The lesson here is profound: fragility can become resilience. What was intended as temporary bookkeeping survived as eternal memory. Antiquity teaches us that what we deem mundane may one day be civilization’s treasure.

Egypt: Writing for the Gods

If Mesopotamia wrote for administration and record, Egypt wrote for eternity. Hieroglyphs carved into stone temples were not merely texts; they were offerings. To carve one’s name on a monument was to secure immortality. For Egyptians, the afterlife was as real as the Nile, and stone inscriptions were passports through eternity.

The pyramids themselves, monumental in their geometry, embody this philosophy. Built not only as tombs but as cosmic symbols, they aligned with stars and solstices, embedding human ambition into the very rhythms of the heavens. Every block of limestone carried both physical weight and metaphysical meaning.

And yet, just as striking is what was erased. Pharaohs often defaced the names of rivals from monuments, attempting to strike them from memory. Stone could immortalize, but it could also annihilate. The act of erasure reveals how powerful memory itself was in antiquity: to be forgotten was worse than to die.

Greece: Beauty as Permanence

The Greeks built less gigantically than the Egyptians, but with subtler intent: to bind beauty and thought into matter. The Parthenon in Athens is a temple, yes, but also an equation. Its proportions embody symmetria and harmonia, mathematical ideals that tied human perception to cosmic order.

Greek inscriptions, too, were not only records but philosophy in stone. Gravestones often carried epigrams—short, poetic reflections on life and death—turning private grief into communal wisdom. A single epitaph could contain more philosophy than entire treatises.

To the Greeks, antiquity’s legacy was not sheer endurance, but the endurance of ideals. Even in ruin, the Parthenon remains an icon of balance, democracy, and reason. Its stones whisper not of empire but of thought.

Rome: Empire in Marble

Rome expanded on Greek ideals but turned them toward power. Where Athens carved temples, Rome built aqueducts, roads, amphitheaters, and arches. Their legacy in stone is practical, imperial, and theatrical all at once.

The Colosseum was not merely entertainment—it was propaganda in limestone and concrete. Every stone set into its walls testified to Rome’s mastery over people and nature. To build in stone was to assert dominance, to claim eternity as a birthright.

And yet, like Egypt, Rome also reminds us of fragility. Their empire fell, but their ruins endured. Roman bridges still stand across rivers, aqueducts still mark landscapes, and their inscriptions still declare victories. Time has stripped away the empire but left behind its skeleton, as if stone itself chose what to remember.

Asia and Beyond: Stone as Sacred Record

While Western antiquity often emphasizes empire, in Asia stone frequently served as scripture.

- India: Emperor Ashoka (3rd century BCE) carved edicts into stone pillars across his empire. These inscriptions, advocating nonviolence, compassion, and religious tolerance, were less about glorifying power and more about guiding moral conscience. Each pillar was a sermon in granite.

- China: Stone stelae preserved calligraphy, embedding not only meaning but artistry. The stone became both page and gallery, a place where brushstrokes could transcend the fragility of paper.

- Mesoamerica: The Maya inscribed stelae with hieroglyphs that fused cosmic cycles with human rule. Their temples aligned with solstices and equinoxes, turning stone into a calendar of the heavens.

Each culture demonstrates that while stone is silent, it can be tuned to many languages: power, philosophy, morality, and astronomy.

Ruins as Teachers

Today we do not use ruins as temples or libraries. Yet we pilgrimage to them. Why?

Because ruins teach. They teach humility—reminding us that even the greatest powers crumble. They teach endurance—showing us that ideas carved in stone outlast empires. They teach paradox—revealing that absence can be as powerful as presence.

Standing before Angkor Wat, the Great Wall, or the pyramids, we sense something beyond history: a dialogue with time itself. In the cracks and shadows, we find our own reflection.

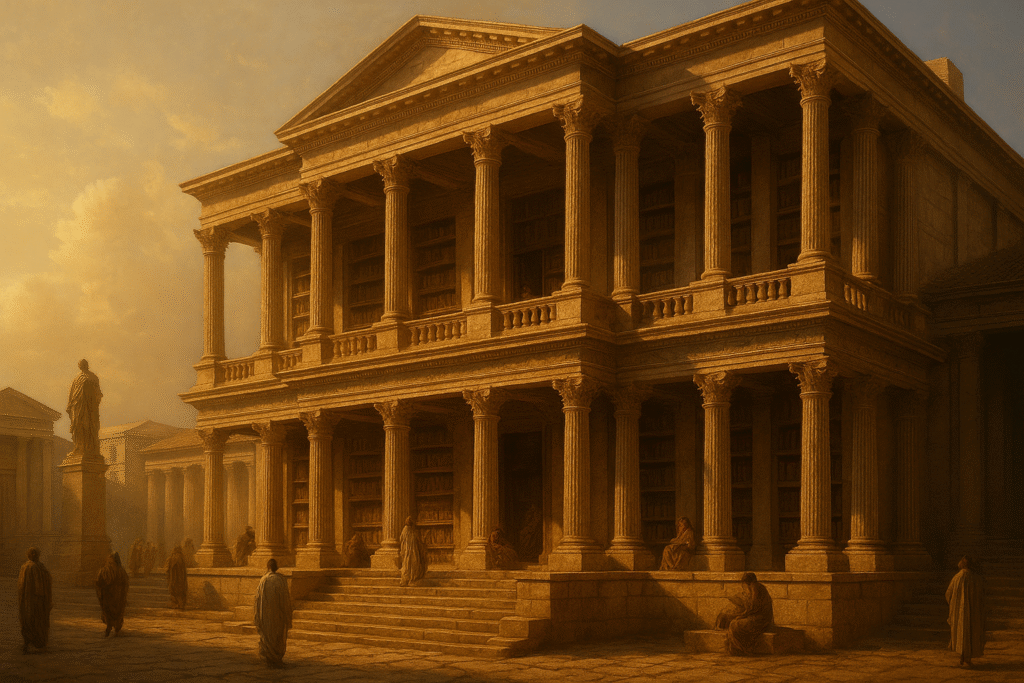

From Stone to Cloud: Modern Memory

Our age preserves memory differently. We inscribe not on stone but on servers. The Internet Archive is our Library of Alexandria, built not with marble but with data. Yet as durable as digital feels, it is fragile: one server crash, one global blackout, and whole eras could vanish.

Stone, for all its limitations, endures storms and centuries. Perhaps this is why ruins fascinate us in an age of ephemera. They are not nostalgic, but prophetic. They remind us that permanence is rare, and that to be remembered requires both material and meaning.

The Philosophy of Antiquity’s Legacy

Antiquity is not just about the past—it is about our dialogue with permanence. Every ruin asks us: what will you leave behind?

Will our skyscrapers endure like the pyramids? Will our digital archives survive as long as Ashoka’s pillars? Or will future civilizations know us only through what we carve into the most enduring medium we have—stone, earth, silence?

The legacy of antiquity is not nostalgia for vanished empires. It is the recognition that humans, across cultures and ages, shared a singular desire: to resist oblivion. Stone became their language. And even now, thousands of years later, it speaks to us, reminding us that memory is the only true immortality.

Reply