When we picture antiquity, the mind often races to the stone giants: pyramids, ziggurats, temples carved into cliffs, statues that stare across centuries. Yet one of the most powerful legacies left to us is not carved in granite or gold but preserved in fragile fibers, clay, and ink: the library. These sanctuaries of knowledge were not simply places to store scrolls—they were engines of civilization, memory made material, and monuments to the idea that wisdom can outlast death.

Today, we walk among ruins of marble, but the libraries of antiquity haunt us differently. They haunt us with absence—with the reminder that much of what humanity once knew has been lost, and that what survives is precious beyond measure.

The Birth of Archives: Mesopotamia and the First Memory Keepers

The world’s first libraries emerged in Mesopotamia, the “cradle of civilization.” In the bustling city of Nineveh, King Ashurbanipal (7th century BCE) gathered a collection of more than 30,000 cuneiform tablets. Each was pressed with stylus marks that carried hymns, omens, recipes, laws, mathematical problems, and epic poetry. The most famous survivor is the Epic of Gilgamesh, a tale of mortality and the quest for meaning that still resonates 4,000 years later.

To Ashurbanipal, collecting these tablets was an act of sovereignty. Knowledge was not only power—it was permanence. Armies conquered land, but libraries conquered time. His library, when discovered in the 19th century, revealed that ancient Mesopotamians pondered the cosmos, dreamed of immortality, and healed with herbal medicine.

But it also revealed the vulnerability of memory. Fire and conquest destroyed much of what was gathered. What we have are fragments, whispers. Still, even fragments prove that voices can cross millennia.

Alexandria: A Dream of Total Knowledge

The Library of Alexandria is perhaps the most famous repository of wisdom in human history. Founded under Ptolemy II in the 3rd century BCE, its ambition was staggering: to gather every text in the known world. Ships arriving at the harbor were searched; their manuscripts copied for the library’s shelves. It is said to have housed works from Greece, Egypt, India, Mesopotamia, even China.

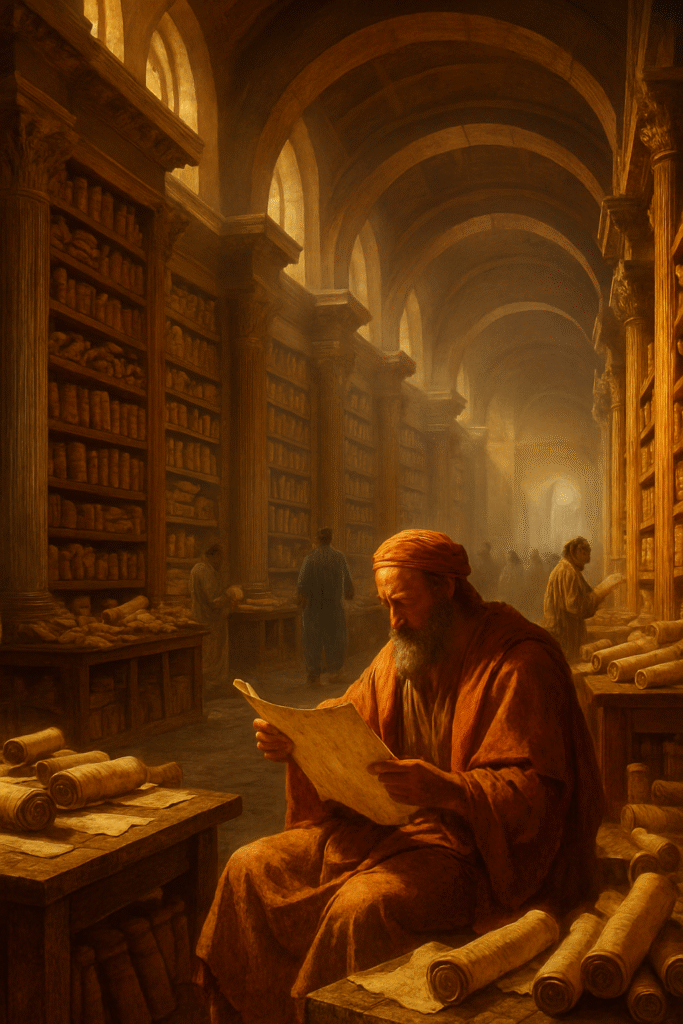

Imagine its halls: scrolls stacked in cedar cases, scholars debating under colonnades, the smell of papyrus and ink mingling with sea salt from the nearby Mediterranean. Within those walls, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy mingled freely.

And yet, Alexandria is remembered less for what it contained than for what was lost. Fires, neglect, political strife—all may have played a role in its downfall. Some say Julius Caesar’s siege sparked the destruction. Others say it withered slowly, scroll by scroll, forgotten as empires shifted.

What matters is not which theory is true, but what the myth reveals: that we fear above all the silence left when memory is erased. The Library of Alexandria has become the greatest symbol of fragility—the reminder that even the loftiest dreams of preserving human thought can collapse into ash.

Knowledge as Sacred Flame

Across the world, ancient peoples treated libraries not as secular archives but as sacred fire.

- In China, the Imperial libraries preserved the Confucian classics and dynastic histories, safeguarding continuity even through rebellion and chaos.

- In India, the great universities like Nalanda (5th century CE) held texts on philosophy, astronomy, medicine, and Buddhist thought, drawing students from as far as Tibet, Korea, and Persia. When it was burned in the 12th century, the library’s ashes were said to smolder for months.

- In Mesoamerica, Mayan and Aztec scribes painted their histories, rituals, and astronomical cycles into codices of bark-paper. Spanish conquest consumed most of these manuscripts in fire, dismissing them as superstition. Fewer than 20 survive.

To burn a library was more than an act of destruction—it was spiritual warfare, an attempt to erase memory itself. Libraries were temples where ink replaced incense, and parchment replaced prayer.

The Philosophy of Memory

Why did ancient civilizations risk so much to preserve brittle scrolls and fragile papyrus? Because they understood something profound: memory is immortality.

Every archive was a bet against forgetting. To inscribe was to declare: This moment matters. This knowledge will outlive me. A scribe hunched over clay in Babylon or papyrus in Egypt was not merely recording words; he was stitching his civilization into the fabric of eternity.

The paradox, of course, is that so much has still been lost. Yet even ruins have power. The fragments that remain remind us that wisdom can leap across gulfs of time. A single surviving line from a lost text can ignite a renaissance centuries later.

Modern Resonance: The Digital Alexandria

Today, in the age of cloud storage and global archives, the dream of Alexandria lives on. Projects like the Internet Archive or the Digital Library of Alexandria aim to preserve humanity’s knowledge in the face of war, censorship, and decay. But the lessons of antiquity still hold. Technology may change the medium, but the challenge remains the same: how to protect memory against oblivion.

The fires of Alexandria whisper a warning: knowledge is fragile. Empires fall, servers fail, and civilizations forget. Yet the impulse to preserve is indomitable. From clay tablets to cloud servers, we continue the same struggle.

The Echo

The true legacy of antiquity’s libraries is not just the texts they held. It is the idea that to remember is to resist time.

Every scroll saved from the ashes, every codex hidden from conquest, every tablet rediscovered beneath the sand is proof of humanity’s refusal to let silence win. Ancient libraries may be gone, but they echo still—in every book we read, every archive we build, every digital record we back up against the dark.

The echo is not just about what was lost. It is about what endures.

Reply