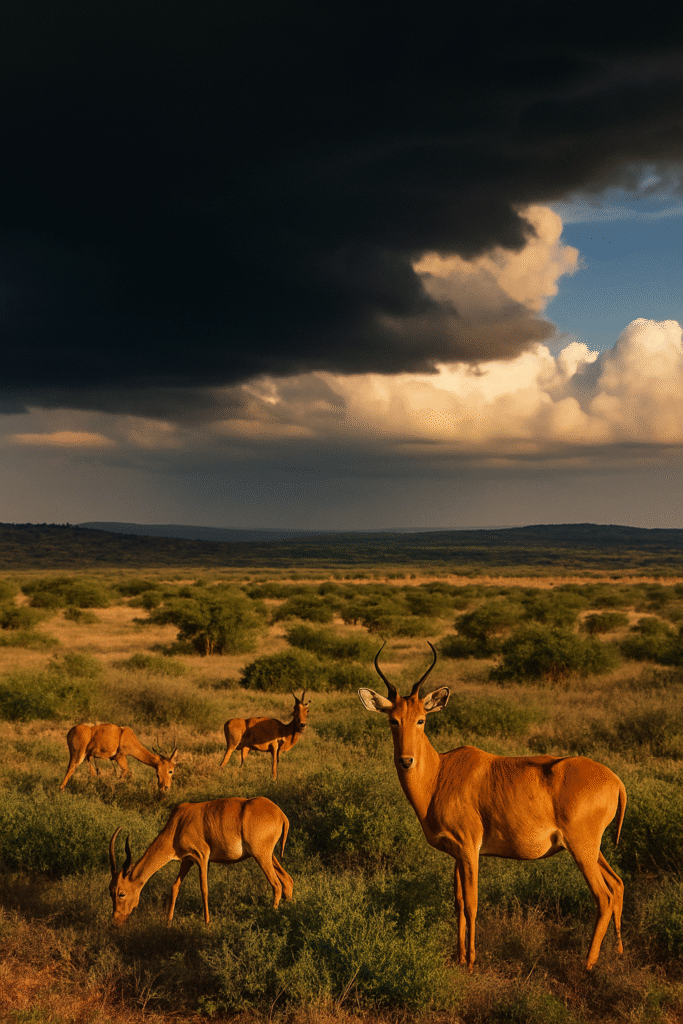

Prologue: a herd on the wind-line

At dusk on the Kenya–Somalia borderlands, wind combs the short grass into silver and the sky folds itself into indigo. A small herd moves low and quiet—cinnamon coats, white spectacles around watchful eyes, black-tipped tails switching with alert metronomy. The animals don’t announce themselves the way larger antelopes do. They read the land and write nothing back. This is the hirola, the last living member of its genus, a relic of grasslands that predate most of what we recognize today. It has outlived rinderpest, drought cycles, and the fall and rise of human boundaries. It may not outlive indifference.

The hirola is not just rare; it is singular. If it goes, an entire evolutionary branch disappears with it.

1) Identity: what the hirola is (and is not)

- Taxonomy: Order Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates), family Bovidae. Genus Beatragus with a single surviving species, B. hunteri. No close living relatives—evolutionarily distinct and globally endangered.

- Look: Medium-sized (adult females ~70–80 kg; males heavier), sleek fawn to cinnamon coat, white “spectacles” around the eyes, pale ear linings, and a clean white line along the underjaw. Both sexes carry ringed, lyre-shaped horns (males thicker, more ridged).

- Gait & digits: Built for elastic, ground-eating canters across open bush-grass mosaics. Hooves narrow and hard for crusted soils and dry pans.

- Voice: A muffled snort when alarmed; soft grunts in close-range signaling. Mostly, the hirola prefers silence as a survival tactic.

To mistake a hirola for a hartebeest or topi is easy at distance; the spectacles give it away up close. The face seems to wear its own binoculars—an adaptation that breaks up the head’s outline in shimmering heat.

2) Range and the architecture of survival

The historical range arcs across eastern Kenya into southwestern Somalia, a belt of open grasslands punctuated by acacia scrub, sandy luggas, and seasonal waterholes. This landscape is not blank; it’s a living spreadsheet of grass height, burn age, and shade patterns. Hirola prosper where:

- Fire is periodic but not constant, creating a quilt of fresh flush and older cover.

- Grass stays short to medium and nutritious (grazers’ guild logic: when grass exceeds knee height, delta of protein collapses).

- Thorn scrub remains patchy—enough for shade and escape angles, not enough to choke visibility.

- Predator pressure is diluted across space and time by open sightlines.

Push the system toward continuous shrub thickening, fixed boreholes that force predictable congregation, or fences that kink migration micro-loops, and you tip the ledger against hirola.

3) Diet and water: fine margins in a dry country

Hirola are selective grazers. After early rains, they target short, protein-rich regrowth—the green edge that follows lightning-struck grass. During late dry seasons, they trim forbs and seedheads, squeezing nutrition from plants that would defeat less choosy mouths.

Water strategy is flexible but tight:

- They drink when they can, especially lactating females and calves, but will range widely to find ephemeral pans after storms.

- In protracted droughts, they track green tongues along drainage lines, sharing risky space with livestock and predators.

The hirola’s metabolism is built for lean seasons—conservation mode by design—but repeated bad years stack like overdue bills.

4) Social structure: small groups, big calculations

Typical groupings include:

- Nursery herds of females, yearlings, and calves (6–20 animals common in modern, fragmented settings).

- Bachelor groups of subadult and non-territorial males.

- Territorial males holding small, scent-marked patches along travel corridors or near preferred feeding flats during peak resource months.

Territories aren’t castles; they’re negotiation tables. Males tolerate transient herds and advertise with dung middens, forehead gland rubs, and sharp horn displays. During drought or high predation, territoriality collapses into cooperative fleeing—the right decision is to move, not to own.

Calving peaks shortly after the first reliable rains. Newborns hide in grass for days, relying on immobility and low scent. Predation risk is highest here—jackals, caracals, hyenas, and lions read the same calendar.

5) Predators, disease, and the ledger of losses

Hirola live in a neighborhood of capable carnivores: lions, cheetahs, leopards, spotted and striped hyenas, jackals, and crocodiles at the wrong river bend. Predation is natural, but its impact multiplies when:

- Shrub encroachment shortens sightlines.

- Livestock and wildlife crowd into few remaining waters, creating predictable ambush sites.

- Drought compresses forage, slowing mothers and drawing herds into repeatable patterns.

Historically, rinderpest—a viral cattle plague—scythed wildlife across East Africa, and hirola were no exception. With the disease now banished from the region, its ghost remains in demographics and memory. Contemporary disease concerns shift to parasites, bovine-associated pathogens at livestock interfaces, and nutrition-linked susceptibility during prolonged dry spells.

6) Why hirola matter: beyond beauty and rarity

- Evolutionary distinctiveness: As the sole representative of their genus, losing hirola is not losing “one antelope”; it’s losing an entire branch of bovid history.

- Grazing geometry: They shape post-burn succession, trimming aggressive grasses and opening space for forbs that butterflies, small mammals, and birds use—a subtle but vital landscape service.

- Indicator species: Hirola presence signals functioning open grasslands with balanced fire, browsing, and predation.

- Cultural fabric: Pastoral communities fold hirola into place-based identity—the animal is part of stories told at water points and in shade corrals.

7) What happened: a concise timeline of decline

- Pre-20th century: Hirola range widely across arid grasslands, fluctuating with rain cycles and herbivore pressure.

- Mid-1900s: Rinderpest, hunting, and changing fire regimes begin compressing numbers.

- Late 20th century: Shrub encroachment, drought clustering at boreholes, and predation in altered habitats produce steep declines.

- Recent decades: Small, isolated herds persist in northeast Kenya with conservation translocations to fenced or semi-fenced sanctuaries for nucleus protection, alongside community conservancies managing wider matrix habitats.

The throughline: habitat function unraveled, predators filled the vacuum efficiently, disease and drought did the rest.

8) What works: a practical, field-tested playbook

1) Habitat first: keep grass open and edible

- Patch-mosaic fire tailored to rainfall years (burn small, staggered blocks; protect drought refuges).

- Targeted bush control (mechanical removal or carefully timed browsing) along key movement corridors and around calving grounds.

- Pulse water rather than permanent year-round points—reduce predator predictability and grazing choke points.

2) Predator–prey balance without illusions

- In small nuclei (founders, insurance herds), use predator-proof sanctuaries or low-porosity fences to let numbers rebound.

- In the open matrix, invest in visibility (shrub management) and escape routes rather than blunt predator removal. Apex carnivores belong; geometry is the lever.

3) Livestock as partners

- Harmonize grazing rotations so cattle pre-trim tall swards, letting hirola target the tender regrowth—classic facilitation instead of competition.

- Herding curfews near calving zones during peak weeks; night corral placement that avoids key travel lines.

4) People paid for outcomes

- Back community conservancies with predictable funding tied to measurable wins: calf survival, group sizes, shrub cover change, and poaching incidents (which are typically secondary but must stay at zero).

- Ranger jobs, grassland monitors, and fire crews come from the same villages that share water and space with hirola.

5) Reintroductions that learn

- Start with founder groups in secure sanctuaries; let numbers cross minimum viable thresholds; export surplus to unfenced conservancies with trained guardians and pre-managed habitat.

- Track individuals with ear tags, collars, and camera grids; adjust release timing to rain pulses, not calendars.

9) Metrics that matter (and keep projects honest)

- Adult female survival across seasons—more informative than raw counts.

- Calf recruitment (calf:female ratios three months after peak calving).

- Shrub cover % within 500 m of water and along known travel corridors.

- Predation signatures (species, location, vegetation context) to guide habitat tweaks.

- Genetic diversity in sanctuary populations to prevent closed-loop inbreeding.

- Community revenue & employment stability—because gaps in payroll equal gaps in patrols.

When boards, donors, and ministries ask “How are the hirola?”, these are the answers that mean something.

10) Fieldcraft: seeing a cautious antelope in a hot mirage

- Time of day: First light and last hour before dark—hirola “talk” most clearly in low wind and long shadows.

- Optics: Heat shimmer lies; get low, triangulate with fixed landmarks, and confirm with the eye-rings flash.

- Signs: Fresh, clipped swards at burn edges; fine pellets in tight clusters; narrow trails threading between short acacia.

- Approach: Quarter across wind; stop often; avoid creating linear pressure. In community lands, always check in first—the best sightings come with local guides who know yesterday’s water and fire.

11) Myths to retire—and truths to keep

- Myth: “Hirola can’t live with livestock.”

Truth: They can, and often do, if rotations are smart and shrub cover is kept in check; cattle can facilitate tender regrowth. - Myth: “Fencing solves everything.”

Truth: Fences protect nuclei; landscapes still need open corridors and community buy-in. - Myth: “Predators are the problem.”

Truth: Predators exploit habitat failures; fix sightlines, water pulses, and crowding first. - Myth: “They’re shy antelopes that will vanish anyway.”

Truth: With habitat managed and communities resourced, hirola breed and grow; the species is cautious, not doomed.

12) Climate realities: designing for hotter, drier swings

Expect wider rainfall swings, harsher midday heat, and longer intervals between reliable grass flushes. Actionables:

- Shade islands protected from browsing to create micro-refuges for heat-stressed herds.

- Emergency grass banks—fenced exclosures opened when forage falls below trigger thresholds.

- Mobile water stewardship to avoid permanent predator hotspots.

- Drought early-warning using satellite green-up indices shared weekly with rangers and herders.

Climate resilience is logistics, not slogans.

13) Quick guide (for your editors & social team)

- Common name: Hirola (Hunter’s hartebeest is misleading; it isn’t a hartebeest).

- Scientific name: Beatragus hunteri.

- Status: Critically Endangered; wild population measured in hundreds, not thousands.

- Range: Bush-grass mosaics of eastern Kenya and adjacent southwestern Somalia.

- Look-for: White eye-rings, slim lyre horns on both sexes, clean jawline stripe, black tail tuft.

- Best chance to see: Community conservancies and carefully managed sanctuaries in northeast Kenya; always travel with approved local guides.

14) What success looks like (and feels like)

Not a ribbon-cutting. A morning. After a night that smelled of petrichor, you glass across a burnt patch flashing new green. Three females step out, heads low, ears like commas, a calf hesitating at the edge then committing with a small jump. Twenty minutes later a male rises from a shade patch you had mistaken for soil and draws a half-moon around them, not herding, just accounting. The wind shifts, everyone lifts their heads in the same second, and the herd flows a hundred meters downlight—no panic, just a change of paragraph. That’s success: time to make choices in a landscape that’s reading them back correctly.

15) How you (and we) keep the ledger in the black

- Support community conservancies that tie ranger salaries and school fees to wildlife metrics.

- Choose travel operators that follow local protocols, hire locally, and avoid pressure near calving grounds.

- Back programs that fund fire crews, shrub control, mobile water, and monitoring, not just vehicles and workshops.

- Tell this story accurately: a unique antelope, a fixable habitat problem, a community-led solution.

Closing: the antelope on the edge of time

Some mammals announce themselves with horns and voice. The hirola announces itself with continuance. It keeps moving, even when the air is a kiln and the grass writes the alphabet of hunger. It is an animal that asks little—short grass, long sightlines, and room to decide. Give it those and the spectacles will flash at dawn for another hundred years. Take them away and the world loses not just a species but a style—a way of being mammal on open ground that we will not see again.

Reply