Rare moment — a ribbon in the tide line

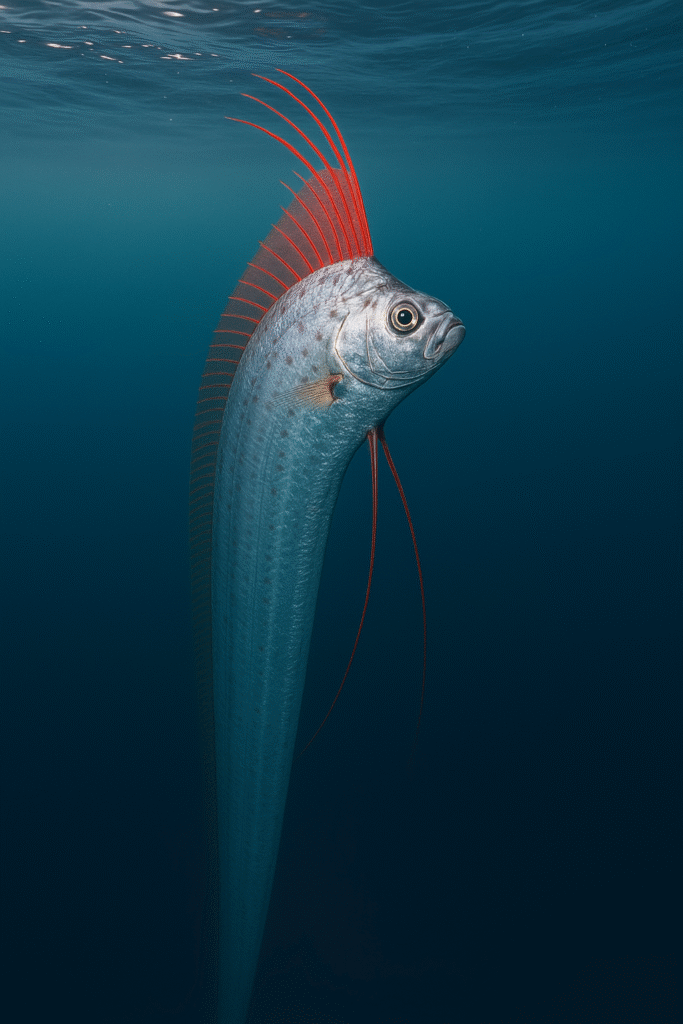

The swell was lazy, the sky undecided. Gulls stitched the horizon in slow white punctuation. Then the water ahead creased, and a strip of silver rose like a banner unfurling from the seabed. At its head, a scarlet crest stood to attention; along its spine, a delicate fin rippled like Morse code. The animal turned not with a tail flick but with a whole-body undulation, thin as a sword blade and twice as precise. For twenty heartbeats we shared a surface with a creature that had previously lived only in sailors’ imaginations. Giant oarfish. The sea spelled the word and then erased it.

Encounters like this are why coasts have legends.

Identity: what the oarfish is (and isn’t)

- World record holder: The longest bony fish, commonly 3–8 m; rare credible reports extend beyond this. Ribbon-slender, not heavy like an oar—its name likely comes from the oar-shaped pelvic fins.

- Habitat: Mesopelagic (roughly 200–1,000 m), worldwide in temperate to tropical seas; occasionally comes near the surface when ill, stressed, spawning, or riding internal waves.

- Build: A silver, scaleless body with a sheen of guanine; continuous dorsal fin running the entire length; an erect red nuchal crest over the head; vermilion pelvic “streamers.”

- Diet: Zooplankton—euphausiids (krill), small jellyfish, larval fishes—captured by gentle suction rather than pursuit.

- Swimming style: Anguilliform wave running from head to tail or slow vertical “fin sculling” with the dorsal—like an elevator ride through twilight water.

- Disposition: Non-aggressive, delicate, easily injured by handling; strandings are usually animals in poor condition rather than healthy curiosities.

This is not a monster or a snake. It is a precision instrument tuned for the slow weather of the mid-water world.

Strange/camouflage: a body built from light and rumor

- Mirror skin: The guanine layer turns the body into a liquid mirror, scattering light and making edges disappear; predators in the dim blue lose the outline.

- Vertical life: Oarfish often hold themselves head-up, as if planted in the water column. This posture likely tunes the lateral line to drifting prey and the dorsal fin to minute stabilizing pulses.

- Crest and streamers: The crimson crest may break the silhouette or serve as species/sex signal during close encounters in the dark.

- Low gear only: Muscles are for endurance, not sprinting. The animal’s answer to danger is mostly depth.

Majestic photography + storytelling: how to shoot a living ribbon

- Find the scene: Strandings occur after storms or internal‐wave events; nearshore encounters happen on glassy mornings with weak swell.

- Keep the water between you: Photograph through the surface; if you enter the water, do so with a guide and wide glass, no flash, minimal kicks.

- Angles that sing: Side-on to show the infinite dorsal fin, low angle for the crest and pelvic streamers; slow shutter on rippling fin for motion blur.

- Ethics: No grabbing. If the fish is in distress and surf conditions allow, guide gently by the tail streamers or with a soft sling, never by the head or gills; prioritize oxygenated flow over hero shots. If waves or crowds make that unsafe, create a clear corridor and call trained responders.

“Rare moment” rescue: the sling and the set

The fish lay crosswise to the incoming swell, rolled each wave like a coin. Two locals rushed in with towels. We asked them to stop—cloth strips strip slime and skin. Instead we formed a human V in knee-deep water, floated a soft tarp under the body, and walked it out until the dorsal fin stood upright again. At the drop-off, the oarfish hovered, then elevatored down in slow, dignified meters. We didn’t cheer. The sea doesn’t clap; it resets.

Rescue checklist (ethical minimum):

- Keep fish submerged; never drag on sand.

- No lifting by head, mouth, or gills; use a sling or cradle.

- Orient head into gentle flow; avoid breaking waves.

- If the fish cannot maintain posture, call authorities—don’t convert a rescue into a spectacle.

Survival battle: a specialist in a world of speed

The open sea’s rule is efficiency. Oarfish win by using little, not by taking much. Their bodies trade armor and burst power for length as sensory antenna, letting a small brain read large volumes of water. Predators—sharks, large billfishes, marine mammals—can outpace them, but in the deep-blue dusk, seeing first means sliding away before pursuit starts.

Strandings short-circuit that rule: internal parasites, warming events, low oxygen, or injuries push oarfish to the surface, where waves and human curiosity are just as deadly as jaws.

What you didn’t know (and will remember)

- Sea-serpent solved. Many historical “serpent” accounts match a surface-swimming oarfish, crest erect, body weaving.

- No scales, no spines. The skin is delicate; a rough grip tears and bleeds fast.

- A dorsal dial. Oarfish can reverse the ripple of the dorsal fin to hold station in variable currents—like rowing a ribbon.

- Gentle mouths. Tiny, toothless jaws are for suction, not biting.

- Spawning in the open. Eggs drift pelagic; larvae look like miniature flagpoles with oversized fins.

- Vertical migrants. Likely rise at night with zooplankton and descend by day, following the ocean’s daily heartbeat.

- Electroreception suspected. Sensory pores and behavior hint at a fine electrical sense, useful in the dark.

- Storm stories ≠ prophecy. Strandings around storms are plausible (mixing, internal waves), but there’s no evidence oarfish predict earthquakes.

- Edible? No. Flesh is gelatinous; in coastal folklore it was considered taboo or at least not worth the firewood.

- Citizen science matters. Proper photos + length/condition notes help researchers piece together a life mostly lived out of sight.

Symbolism, culture, mythology

Pacific islands tell of sea dragons that surface before big weather; Scandinavian sailors spoke of ribbonfish that presaged luck or loss. In Japan, ryūgū no tsukai—the “messenger from the palace of the sea god”—is the oarfish in ceremonial clothes, a bearer of meaning. Myth thrives where observation is sporadic and astonishing. Today we can give the legend a substrate: a real animal with a physics you can film. The story becomes richer, not smaller.

Field guide: where and how rare becomes possible (without pin-dropping)

- Where (general): Subtropical and temperate coasts with steep bathymetry—islands, fjords, seamount lines.

- When: Days after storms with strong internal mixing; glassy dawns with weak swell.

- Signs: A vertical silver blade in the water; red crest or streamers near the surface; undulating, unhurried motion.

- Etiquette: No crowding; one or two observers is enough. Give way to trained responders. Never tow by a boat unless instructed—prop wash damages fins.

Threats: the modern ledger

- Warming and low oxygen in mid-water layers stress endurance specialists.

- Light pollution (deep fishery lamps) may disorient vertical migrants.

- Bycatch in large mid-water nets is poorly recorded; carcasses often do not reach shore.

- Coastal spectacle—handling by crowds turns survivable strandings into fatalities.

The oarfish is not targeted, but it is collateral in seas tuned for industrial light and speed.

What works (practical, proven)

- Response protocols for strandings: lifeguards and harbor teams trained with soft slings, head-into-flow releases, and crowd control.

- Night-light limits in mid-water fisheries where feasible; research into spectra that spare non-targets.

- Acoustic/light-free corridors along steep coasts during plankton blooms when vertical migrants are thick.

- Citizen-science reporting: standardize photos (side-on, head crest, pelvic fins), note GPS/time/sea state, and condition (alive, weak, dead).

- Public storytelling that swaps superstition for stewardship—if you meet a “sea serpent,” become a guardian, not a collector.

Majestic photography: a micro-playbook

- Lens: 24–70 for in-water proximity; 70–200 from a deck.

- Shutter: 1/250–1/500 to freeze crest ripples; slower (1/60) for an artistic fin wave blur.

- Polarizer: Cuts surface glare; angle 30–40° off the sun.

- Alt text ideas: “Giant oarfish vertical in glassy water with red crest,” “Close detail of dorsal fin ripples,” “Rescuers guiding oarfish with a soft sling.”

Climate realism: twilight habitats under new rules

As mid-water layers warm and deoxygenate, the depth bands oarfish use may sink or fragment. The cure is not species-specific: reduce emissions, protect upwelling systems, and curb nutrient runoff that drives low-oxygen events. Twilight communities are the scaffolding for tuna, whales, and seabirds; saving them saves more than a legend.

Personal narrative + moral

When the oarfish finally pivoted and slipped below, it did something impossible to photograph: it removed drama from itself and became part of the water. I stood with my camera slack and realized the creature’s gift was not spectacle but scale—a reminder that the ocean still carries lifeways we haven’t learned to hurry.

Moral: If you meet a legend, guard its exit. Teach crowds. Train responders. Keep mid-water dark and breathable. We don’t need to own the sea’s mysteries to prove they exist; we need to leave enough quiet for them to keep happening.

Fast FAQ

Is the giant oarfish dangerous?

No. It lacks teeth suited for biting and avoids conflict. It’s fragile; we are the danger.

Why do oarfish wash ashore?

Likely illness, injury, temperature/oxygen stress, or spawning events—not earthquake prediction.

Can they be kept in aquariums?

No. Their size, fragility, and mid-water lifestyle make captivity unsuccessful.

What do they eat?

Small planktonic animals—krill, pelagic larvae, gelatinous zooplankton—sucked in rather than chased.

How can I help if I see one?

Call local marine rescue. Keep the fish in water, create space, and, if trained, assist with a soft-sling release.

Closing

For centuries the sea offered stories of serpents in shining mail. The giant oarfish is the truth inside that poetry: a ribbon of muscle and mirror that writes one quiet line on the surface and then returns to the page below. If we keep the mid-water world breathable and our shorelines kind, the legend remains alive—not in museums or myths, but in the exact moment when a red crest breaks a green sea and your pulse tries to remember an older language.

Reply